"George" by George.

" . . . In a letter to his first love, Mary Hamilton, written when he was 16, he described himself as follows:

"Your brother is now approaching the bloom of youth. He is rather above normal size, his limbs well proportioned, and upon the whole is well made, though he has rather too great a penchant to grow fat. The features of his countenance are strong and manly, though they carry too much of an air of hauteur. His forehead is well shaped, his eyes, though none of the nest, and although grey are passable. . . His sentiments and thoughts are open and generous. He is above doing anything that is mean (too susceptible, even to believing people his friends, and placing too much confidence in them, from not yet having contained a sufficient knowledge of the world or of its practices), grateful and friendly to an excess where he finds a real friend. His heart is good and tender if it is allowed to show its emotions. . . Now for his vices, rather let us call them weaknesses. He is too subject to be if a passion but he never bears malice or rancour in his heart. As for swearing, he has nearly cured himself of that vile habit. He is rather too fond of Wine and Women, to both which young men are apt to deliver themselves too much, but which he endeavours to check to the utmost of his power. But upon the whole, his Character is open, free and generous." (Perdita: The Literary, Theatrical, Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson: 97)

Handsome and possessed of a great charm.

"George IV was the first Hanoverian monarch to be considered completely English. He was handsome, and possessed of a great charm. His admirable qualities were offset by willful stubbornness, indolence, and insensitivity to all that was not self-serving. His father George III tried to curb his extravagant excesses, and that led to a permanent alienation of father and son; the relationship was usual for Hanoverian kings and their crown prince." (Lives of England's Reigning and Consort Queens: 566)

The First Gentleman of Europe: a fashion trendsetter.

"George Prince of Wales was intelligent and had a gift for learning languages. He was precise in use of English, and fluent in French, German, and Italian. He had a good command of history. He loved the theater of Sheridan and Shakespeare. He was famous for setting fashions of rich elaborate dress, and in his youth, he was called 'The First Gentleman of Europe.' x x x Prince George's love of extravagant ornamentation was reflected in The Regency Style of 19th century English dress, architecture, and interior design. Above all, he was determined to make London equal to, or surpass the most magnificent capitals in Europe. Prince George was regent during the final defeat of Napoleon, which marked a high point in England's prestige." (Lives of England's Reigning and Consort Queens: 566)

"The Prince, though unfailingly supportive during the Seymour Case, had become less 'captivated'. He had had several lovers during those years: the dancer Louise Hilliston, the French wife of the second Earl of Massereene, and a Madame de Meyer whom he had established in an apartment in Duke Street. He had never accepted the paternity of the sons of Mrs. Crewe, Mrs. Davies and Elizabeth Crole. Maria had not been in total ignorance of all this, and, though choosing to ignore his petits amours, the thought of these women and their babies might well have caused that look of unhappiness that had made Mrs. Calvert wonder." (The King's Wife: George IV and Mrs Fitzherbert: 113)

Was George IV a libertine?.

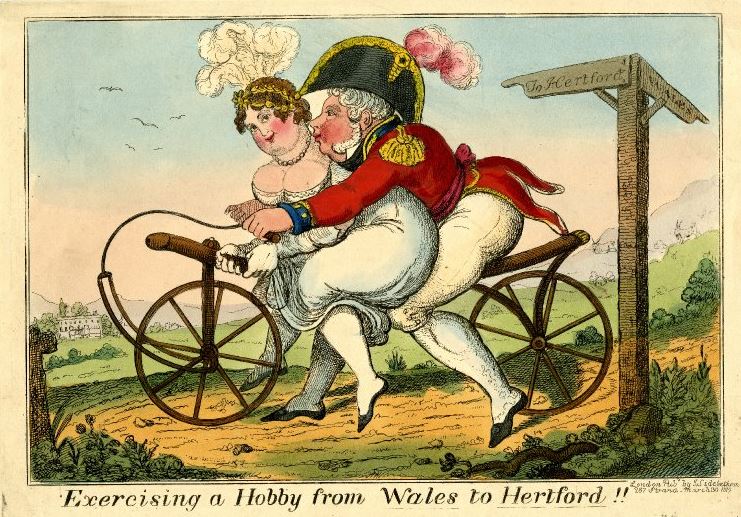

"Was he a libertine? He had mistresses throughout his life. This would make him no different to many other aristocratic men, including Wellington, the hero of Waterloo. The use of taxpayer's money was the main difference. His first mistress was Mary Robinson, an actress to whom he gave extravagant gifts of money. Later she used his love letters to blackmail him. Grace Elliott was a scandalous member of the court set, by whom the prince may have had an illegitimate child. Lady Melbourne also had an affair with the Prince of Wales during the period 1780 to 1784. At the same time as Lady Melbourne, Elizabeth Armistead, wife of his friend and political ally Charles James Fox, was the prince's mistress. Later, as king, George gave Elizabeth a pension of 500 pounds per year. Frances, Lady Jersey, was his mistress when he married Princess Caroline of Brunswick for money in 1795. In the period of his regency, his main paramour was Isabella, Lady Hartford, who lasted until he became king in 1820. His affair with her was common knowledge and satirical cartoons could be bought on the street for pennies. Cartoons show them on a new style bicycle, the velocipede, going on a journey from 'Wales to Hertford'. Another shows the prince handing over the content of the privy purse to his lover at her home at Manchester House. In the eyes of the establishment, the prince's sin was not his behaviour, but his unwillingness to show any discretion." (Dark Days of Georgian Britain: Rethinking the Regency: 80)

Dalliances with the select of the aristocratic class.

"Royal mistresses were often upper-class married women. The Prince of Wales in the late eighteenth century worked his way through Lady Augusta Campbell, Harriet Vernon, Lady Melbourne, the Duchess of Devonshire and the actress Mrs. Robinson, before he reached the age of 21. Later he went on to Mrs. Armistead, Mrs. Billington, Mrs. Crouch, then Mrs. Fitzherbert, whom he married (illegally). Lady Jersey succeeded Mrs. Fitzherbert, then came the Prince's legal marriage (after which Lady Jersey still acted as his mistress, until he returned to Mrs. Fitzherbert for a time). Lady Hertford succeeded Mrs. Fitzherbert, and she in turn was supplanted by Lady Conyngham, who was known as the Vice-Queen when the Prince became George IV, and who survived as mistress until the King's death. . . ." (Perkin. Women and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century England: 92)

A round robin of three most famous courtesans.

"The Prince shared with Fox, Lord Cholmondeley, and Lord George Cavendish a round of the three most famous courtesans of the era: Perdita, grace Dalrymple, and Mrs. Armistead. Georgiana heard that Lord George had paid a drunken visit to Mrs. Armistead one night only to find the Prince hiding behind a door. Luckily, rather than take offense he burst out laughing, made him a low bow, and left. The Prince also pursued Lady Melbourne and Lady Jersey, or perhaps it was the other way round. Less well-informed people speculated that Georgiana was in competition with her friends for the Prince.s affection, but a letter from Lady Melbourne suggests collusion rather than rivalry." (The Duchess: 78)

First public affair and a secret attachment.

"He [George III] could not, however, forbid his son [George IV] to see his uncle and the Prince continued to do so, though hardly needing lessons from him when it came to living for pleasure. He had seduced one of his mother's ladies in waiting when he was sixteen, and then embarked on a series of passionate attachments. His first public affair was with the actress, Mary Robinson, but she had been preceded in the Prince's affections by a secret attachment to Mary Hamilton, to whom he had written daily letters declaring no one had ever loved before as he loved her: 'I love you', he had vowed, 'more than ideas or words can express. . .' Miss Hamilton wisely refused all gifts except friendship; and was easily dismissed with 'Adieu, Adieu, Adieu, toujours chere.'" (The King's Wife: 34)

Preference for older, motherly mistresses.

"George's notorious treatment of his legion of mistresses is easy to censure. His first serious affair was at the age of 17, and by the time he came of age in 1783 he was well-known as an inveterate ladies man who would woo his targets ardently, promise them his eternal love - and a sizeable pension - and then brusquely drop them when he tired of their charms. The whole royal edifice of sexual respectability and family values which George III had worked so hard to create in the 1760s and 70s was rapidly demolished by his son and heir, brick by brick. And, significantly, as he grew older George's marked preference was not for younger, libidinous lovers but for older, motherly mistresses who were able to offer a degree of sympathy and understanding which had never received from his own, coldly calculating mother, Queen Charlotte." (BBC History)

The blessings of being a royal favourite.

All these women sailed around in glory as long as they were favourites; they had great power and were very proud of their situation; they collected money and jewellery, found jobs for their friends and relations, and married off their children and relatives advantageously. They were acting no differently from any other upper-class person with patronage. And this tradition was revived later in the century by the mistresses of Queen Victoria's son, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales." (Perkin. Women and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century England: 92)

"Girls had always been attracted to George IV. At 17 he was said to have seduced one of his mother's maids of honour, written love letters every day to the Duke of Hamilton's great-granddaughter, and fallen violently in love with and promised 20,000 pounds on coming of age to -- a pretty actress, Mary Robinson. She got 5,000 pounds and 500 pounds annuity in the end. Other affairs followed: names include Lady Augusta Campbell -- the Duke of Argyll's daughter; Lady Melbourne -- who may have given birth to his son; Lucy Howard -- whose son, George, supposed to have been his, died young; Louise Hillisberg -- the dancer; Harriet Wilson -- the courtier; Elizabeth Billington -- the singer; Mrs. Anna Maria Crouch -- another singer; Mme de Meyer; the Countess of Salisbury; the Countess of Jersey; Count Karl August von Hardenberg's wife; the Earl of Massereene's wife; Sir Charles Bamfylde's wife; Lord Hertford's wife; Lord Conyngham's wife. George may or may not have succeeded with the Duke of Devonshire's wife. Most husbands were willing and well paid. . . ." (Human Biology and History: 81)

|

George IV of Great Britain

@RA250 |

George IV's lovers were:

British aristocrat, royal courtier & diarist.

Daughter of Charles Hamilton & Mary Catherine Dufresne

Wife of John Dickenson, mar 1785

"Mary Hamilton was born in 1756 to Charles Hamilton (1721-1771), son of Lord Archibald Hamilton; and Mary Catherine (d.1778), daughter of Colonel Dufresne, aide-de-camp to Lord Archibald Hamilton. Growing up, Hamilton was educated, popular, and an avid correspondent. In 1777, she had been asked by Queen Charlotte to come to court in order to assist with the education of the younger princes and princesses." (Royal Collection Trust)

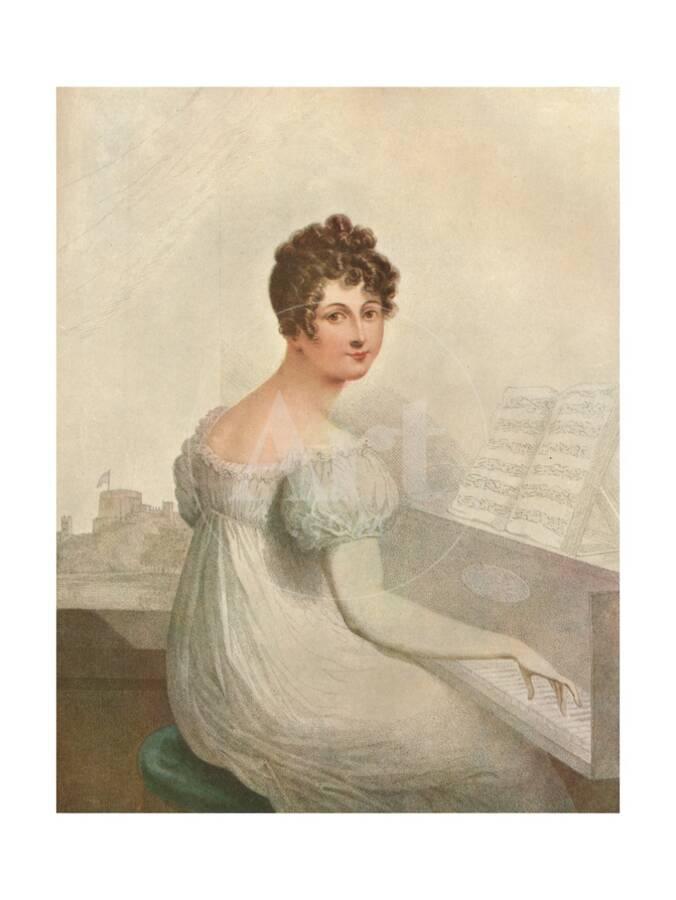

" . . . The first intimations of the Prince's becoming involved in a tangible love affair came in November 1779 with the rumours of his infatuation for Mary Hamilton, one of the ladies attached to the Court. She was a jolly, sensible, attractive girl seven years older than the Prince, who was then not quite seventeen. Her Diary records his pursuit of her with a passion that increased as she strove to discourage his advances. 'My God,' she wrote, 'what will become of you if you suffer yourself to be led away with such impetuosity?' Mary Hamilton's resolution not to give way to the Prince's appeals, although she was unquestionable flattered by his attentions, was never finally put to the test, for in a very few weeks that attraction of a girl encountered for brief moments only in the bustle o f life about the Court gave way to the promise of more substantial delights that offered with the more easily accessible person of Mary Robinson, the pretty actress whom he had met at the theatre while she was playing the part of Perdita in The Winter's Tale. With his final letter to Mary Hamilton, we realise that his passionate outpourings were not so much expressions of love addressed to another living being, but rather colloquies with himself on the idea of being in love with love, for in his last missive telling her that he had fallen in love with another person he ends somewhat surprisingly with the words 'Adieu, adieu, adieu, TOUJOURS CHERE, oh! Mrs. Robinson.'" (Musgrave. Life in Brighton)

"Mary Hamilton was a member of an old aristocratic family. She was born in 1756, the daughter of Charles Hamilton a soldier who had fought as a volunteer for the Empress of Russia and the son of Lord Archibald Hamilton and grandson of the third Duke of Hamilton. Her mother was Mary Catherine Dufresne, the daughter of Colonel Dufresne, aide-de-camp to Lord Archibald Hamilton. After her father’s death in 1771, she and her mother initially settled in Northamptonshire and then later moved to London. One of Hamilton’s uncle's was Sir William Hamilton who as well as being the British Ambassador to Naples from 1764 to 1800 was also an avid art collector. [He was also the husband of Lady Emma Hamilton, née Lyon]. Another uncle was Lord Cathcart, the English Ambassador at the court of St Petersburg. The Duchess of Atholl, Lord and Lady Stormont, Lady Frances Harpur and the Countess of Warwick were all her near relations.Hamilton began her ‘public’ life as an employee in the court of George III. From 1777 until 1782 she was employed as a sub-governess to the young Princesses there. She was a popular figure at court not only with her colleagues but also with the royal family including the Princesses in her charge who nicknamed her ‘Hammy’. Also whilst there, the young Prince of Wales fell in love with Hamilton and inundated her with letters. [Hamilton refused his attentions and he later became involved with the actress Mary Robinson.] Hamilton's position at court was tiring and restrictive and although loyal to the royal family Hamilton resented her lack of freedom. She found life at court tiring and stifling. She also resented the politics of court and noted that it is quite an ‘instruction one gains by living in such a school’ as this. At an early stage as a governess she offered her resignation to the Queen but was persuaded by her not to leave. After receiving a letter from Hamilton asking to be ‘let go’ the Queen responded in a note stating that she attributed her request to her having low spirits. It took three years before the Queen would eventually let her go. After her ‘emancipation' from court, Hamilton lived as an independent woman, setting up house in London at Clarges Street with two sisters and friends of hers, the Miss Clarkes. Although they shared a house, they lived independently of each other. The house was opposite that of the 'bluestocking', Elizabeth Vesey who Hamilton visited almost on a daily basis. The majority of Hamilton’s diaries in this archive (HAM/2) cover the period after her leaving court up to her marriage to John Dickenson in 1785 and are full of detailed entries of her day-to-day life and social engagements. She often attended bas bleu parties and wrote of the conversations and evenings spent with such public figures as Horace Walpole, Elizabeth Carter, Hannah More and Samuel Johnson. Hamilton dedicated much of her time in London in the company of her friends such as Mary Delany, Hannah More and Eva Maria Garrick and of attending the theatre [including having the use of Mrs Garrick's box to watch Mrs Siddons], attending lectures, concerts and exhibitions and with her own literary pursuits." (Archives Hub)

"In April 1779, the 16-year-old Prince fell in love for the first time, with 23-year-old Mary Hamilton, the great-grand-daughter of the 3rd Duke of Hamilton and his sisters' sub-governess, whose virtue was as unblemished as her beauty'. On 25 May, no longer able to hide his feelings, he came clean in a letter:" (NYT)

"A niece of Emma, Lady Hamilton, the famous mistress of Lord Nelson, her alluring looks quickly drew her to the attention of the teenage Prince Regent, later to become King George IV. In spite of the fact that Mary Hamilton was six years his senior, the infatuated youth sent her 78 passionate letters, clearly rehearsing some of the seductive skills that were to earn him a playboy reputation in adulthood." (The Guardian)

"George's first attachment was at age sixteen to. Mary Hamilton, niece of Sir William, one of his sisters' attendants, who was six years older than he was. He wrote her a series of sentimental letters and offered her gifts, but she was too sensible and virtuous to encourage such a youthful infatuation and he turned his attention elsewhere. . . ." (George IV:17)

" . . The future George IV was only 17 when he and Robinson began their year-long affair, but he had already been intimate with Mary Hamilton ('sub-governess' to his sisters), to whom he wrote, 'I am and ever shall be unto my last health Thy Palemon toujours de meme.' A week later, he had changed his mind, dazzled my Mary Robinson's onstage Perdita ('I can not help adoring her') in Garrick's version of The Winter's Tale." (Telegraph) |

Mary Robinson at 25 |

Mary Robinson

(1757-1800)

Lover in 1780-1781.

1st public royal mistress of the Prince of Wales

English actress, poet, dramatist, novelist & celebrity figure.

Daughter of Nicholas Darby (aka John Darby), a Royal Navy captain, & Hester Vanacott (aka Hester Seys)

Wife of Thomas Robinson, an illegitimate child, mar 1774.

Perdita's other lovers.

1. Banastre Tarleton, 1st Baronet (lover in 1783-1797)

2. Charles James Fox

3. George Capel-Coningsby, 5th Earl of Essex

4. George Cholmondeley, 1st Marquess of Cholmondeley

5. Robert Spencer..

First encounter with the Prince of Wales.

" . . . [S]he gained popularity with playing in Florizel and Perdita, an adaptation of Shakespeare, with the role of Perdita (heroine of The Winter's Tale) in 1779. It was during this performance that she attracted the notice of the young Prince of Wales, later King George IV of the United Kingdom.[9] He offered her twenty thousand pounds to become his mistress . . . However, the Prince ended the affair in 1781, refusing to pay the promised sum. . . ." (Wikipedia)

"Mary Robinson appeared in her most famous (and infamous) role at age 21, a four-year veteran of the stage. Her success as Perdita in A Winter's Tale led to a royal request for a command performance. On December 3, 1779, the 17-year-old Prince of Wales (later King George IV) determined to make her his mistress. Lord Malden was sent to negotiate with her on the Prince's behalf. A hot exchange of letters ensued between "Perdita" and "Florizel", and the prince paid her marked attentions in public. Paparazzi of the time, such as the Morning Post and Morning Herald, were quick to scent a scandal, and began to link her with both the prince and Lord Malden. In addition to letters vowing eternal affection, the prince sent gifts which included a miniature portrait, set in diamonds, and a bond of £20,000, to be paid when he came of age. At one point, Mary Robinson became ill, something that often happened when she was under severe stress. Eventually, however, she agreed to become the Prince's mistress. The newspapers followed the relationship with glee, publishing sometimes daily notes on its suspected progress." (A Celebration of Women's Writers)

Affair's end & aftermath.

" . . . George Had been keeping mistresses since 1779, when he met Mary Robinson while she was performing in a play. He offered her twenty thousand pounds if she would become his mistress. George had tired of her within a year, and dumped her without paying her. The affair had ruined her reputation and she wasn't able to find work, so she threatened to sell some of his love letters to a newspaper, and he agreed to pay her a small pension. . . . " (Top Ten Philandering English Monarchs)

"The Prince's defection left Mary Robinson in a difficult position. Both the Robinsons were living on borrowed money, deeply in debt. She had ruined her reputation and given up a promising career as an actress, and received only promises in return. The Prince might have been expected to make some provision for his ex-mistress, but he did not. Her reputation already destroyed, Mary Robinson seems to have cared little about causing further scandal. She demanded £25,000 for the return of the prince's letters. She apparently settled for £5,000, paid by George III "to get my son out of this shameful scrape." It was enough to stave off her creditors. In 1782, Mary obtained a further £500 annuity for herself, and a £200 annuity during the life of Maria Elizabeth, in return for the surrender of the Prince's bond." (A Celebration of Women's Writers)

" . . . Throughout his life he had a series of mistresses, the first of which was Mary Robinson when he was 18 years-old in 1780. She was an actress and said to be extremely witty with very long dark hair. He saw her in a performance at the Drury Lane Theatre and started sending her expensive gifts. As the affair progressed he decided to write her a bond for 20,000 guineas, which was a lot of money in those days. However, when the affair was over the Prince took the bond back and instead gave her an annuity of 500 pounds per annum. . . ." (Fascinating History)

"But it was only a matter of time before the Prince tired of the eccentric Mrs Robinson. Unsavoury incidents, as when she attacked her husband in public after discovering him making love to a `fillette' in a box at Covent Garden, hardly endeared her to her royal lover. As the year drew to its close, the Prince wrote to tell her that they must `meet no more', citing her rudeness to a friend of his in public as the reason. Others believed the rumour that she was also sleeping with his friend Lord Malden. In any case, the Prince had fallen for another woman: the alluring Elizabeth Armistead." (NYT)

Personal & family background.

"The next object of his passion was Mary Robinson, 21, a young actress `more admir'd for her beauty than for her talents'. Though she often hinted that she was the natural daughter of the 1st Earl of Northington, her actual father was almost certainly Nicholas Darby, a Newfoundland-born ship captain, who had abandoned his family after a failed attempt to establish a whale fishery on the coast of Labrador. Married at 15 to Thomas Robinson, an extravagant articled clerk who lived beyond his means, she had been `driven to the stage' to make ends meet. After being released from a long spell in the Fleet debtors' prison, a mutual friend had introduced her to Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the successful playwright who had just taken over from David Garrick as the manager of the Drury Lane Theatre. Sheridan saw her potential, and in December 1776 she made her stage début as the lead in Romeo and Juliet to great acclaim. Within three years she was one of the most celebrated actresses in London, with a habit of riding about town in a carriage adorned by a fake coat of arms, dressed in an array of bizarre yet alluring costumes, and accompanied by her disreputable husband and a host of would-be lovers."

" . . . Prince George's affair with the actress Perdita Robinson cost King George III the very large sum of five thousand pounds---the amount the actress demanded for the return of the prince's letters to her, letters full of erotic effusions. In addition, the king was forced to arrange for Perdita and her daughter to receive income for life. It was not so much the money that was galling to the monarch---though the frugal King George III was angered at the outlay---but the immorality, and the scandal. Prince George's liaison with Perdita gave fodder to the London gossips for many months, and the gossip threatened to undermine the high moral tone the king had always attempted to maintain." (Royal Panoply: 263)

"This life lasted about two years, when just as the Prince, on his coming of age, was about to take possession of Carlton House, to receive 30,000 pounds from the nation towards paying his debts, and an annuity of 63,000 pounds, he absented himself from Perdita, leaving her in ignorance of the cause of his change, which was none other than an interest in Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott." (A Celebration of Women Writers)

(1751-1818)

Viscountess Melbourne.

Lover in 1780-1783.

"The prince, however, had moved on. One of his next conquests was Elizabeth Lamb, Viscountess Melbourne and wife of Peniston Lamb of Brocket Hall, that great friend of Sir John Eliot's. The Lambs had separated shortly after their marriage and Viscountess Melbourne's son George, born in 1784, was reputed to have the Prince of Wales as his father. Grace's world was a small one! One wonders how bitterly the conversation over the dinner table between Sir John Eliot and his friend Peniston Lamb may have turned to their respective wives, one divorced and one separated but both with a child reputed to have been fathered by the Prince of Wales." (An Infamous Mistress)

. . . Certainly the Prince of Wales did. He visited her frequently, traveling by horseback from Carlton House, and sometimes stayed until three or four in the morning. In the early 1780s they became lovers. The thin black velvet band that she wore around her neck in numerous portraits was said to be a symbol of this attachment. . . Somewhat tactlessly, the prince even confessed to Lady Melbourne his infatuation for Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert in December 1785. That same month he married the Catholic widow in a secret ceremony." (Byron's "Corbeau Blanc": The Life and Letters of Lady Melbourne:2)

Benefits and beneficiaries: "Lady Melbourne made use of her political influence in a number of ways. After he love affair with the Prince of Wales subsided into a lifelong friendship, she used her contact with Carlton House to see her husband appointed an Irish viscount (1770), lord of the bedchamber (1784; 1812), and finally, an English peer (1816). In 1791 she agreed to exchange homes with the Prince of Wales' brother (Frederick, duke of York), and the Prince of Wales returned the favor. He lent her his home in Brighton to recover when her eldest son, Peniston, died of consumption in 1805. Through Lord Wellesley, the prince offered her son Frederick a position in the diplomatic line in 1811, and another son, William, a position in the treasury department the following year." (Byron's "Corbeau Blanc": The Life and Letters of Lady Melbourne: 2)

"George IV was the father of Lady Melbourne's fourth son, George (1784). Their affair lasted from 1780 until 1785 and subsided into a lifelong friendship. It was at his urging that Lady Melbourne swapped homes with the prince's brother, the duke of York, in 1792. The two lovers exchanged paintings of one another, and a Reynolds portrait of George IV when Prince of Wales can still be found at Brocket Hall. As Prince Regent, George IV was a close friend of Lady Melbourne's husband, appointing him first gentleman of the bedchamber (1783-96) to the Prince of Wales; lord of the bedchamber (1812-28); and a peer of the realm (1816). He tried to appoint William to the Treasury Board in 1812, which William turned down, and made nominal efforts to advance Frederick Lamb's diplomatic career." (Byron's 'White Raven ': 434) |

Christiane von Reventlow Countess of Hardenberg |

Lover in 1781.

Daughter of Christian Ditlev of Reventlow & amp; Ida Lucie Scheel von Plessen

Who seduced who?.

"One of his earliest escapades, with overtones of comedy if not farce, was his seduction (or possibly hers of him) in the early summer of 1781 of Madame Hardenburg, the wife of the Hanoverian Minister in England. He described in detail to Frederick how after meeting her at a card party in the Queen's apartments he was struck by a 'fatal tho' delightful passion . . . in my bosom . . . for her . . . . O did you but know how I adore her, how I love her, how I would sacrifice every earthly thing to her; by Heavens I shall go distracted: my brain will split.' She resisted his advances at first but probably only to increase his ardour. When he made himself ill with his longing for her . . . she, as he put it, completed his happiness. . . Unfortunately the press got hold of rumours about the affair and lady's husband faced her with the accusation that she had cuckolded him. She was forced to admit that the Prince had 'made proposals' to her and Hardenburg wrote an angry letter to him. . . Nevertheless he wrote to assure Hardenburg that he was the only person to blame for the affair and that she had treated him 'with ye utmost coolness' . . . . " (George IV:20)

Affair's impact on the husband.

"In 1778, Hardenberg was raised to the rank of privy councillor and created a graf (or count). He went back to England, in the hope of obtaining the post of Hanoverian envoy in London; but his wife began an affair with the Prince of Wales, creating so great a scandal that he was forced to leave the Hanoverian service. In 1782 he entered the service of the Duke of Brunswick, and as president of the board of domains displayed a zeal for reform, in the manner approved by the enlightened despots of the century, that rendered him very unpopular with the orthodox clergy and the conservative estates. In Brunswick, too, his position was in the end made untenable by the conduct of his wife, whom he now divorced; he himself, shortly afterwards, marrying a divorced woman." (Wikipedia)

" . . . He also embarked on another ill-advised affair with a married woman, this time with Countess von Hardenberg, the wife of a Hanoverian diplomat, who began to talk of 'running away together'. George was tempted but when he confided in his mother she had her husband send the von Hardenbergs back to Germany, where the Countess then tried her luck with George's younger brother, Prince Frederick." (Great Survivors: 144)

A Spring love affair.

"The Prince also had an ill-advised liaison with Countess von Hardenburg, the artful wife of Count Karl who had come to London in the hope of being appointed Hanoverian Envoy. His first meeting with the Countess was at a concert in the Queen's apartment in Buckingham House during the spring of 1781. After having conversed with her some time I perceived that she was a very sensible, agreeable, pleasant woman, but devilish severe,' he wrote to his brother Frederick in July, after the affair was over. `I thought no more of her at that time.' But at a second meeting at one of the Queen's card parties at Windsor, the Prince, revised his earlier opinion. She looked 'divinely pretty' and he `could not keep' his `eyes off her'. The fact that she, like him, was clearly bored, preferring to play cards for money, served only to increase the attraction'. From that moment,' he wrote, `the fatal though delightful passion arose in my bosom for her, which has made me since the most miserable and wretched of men.' The infatuated Prince made his move soon after, during the fortnight when the Count was the hunting guest of the King at Windsor. Suggesting to the Countess that they meet alone in her husband's house in London, he was taken aback by her angry response that he had forgotten to whom he was talking, and was forced to apologise. But it was all for effect. The Countess was a capricious minx, by turns seductive and aloof, who, soon after Prince Frederick's arrival in Hanover, had tried to make love to him at a dance. When the moment proved inopportune — the room to which they retired was already occupied — the Countess flounced off and told an acquaintance that Prince Frederick was `the most tiresome fellow' and `never would leave her alone'. The Prince's response was as expected. Far from lessening his affection, it had 'increased it if possible', and made him `entertain a higher idea of her honour'. Nevertheless, it still took another two or three visits before the scheming Countess would let him make love to her. `However,' he informed Prince Frederick, `at last she did. O my beloved brother, I enjoyed beforehand the pleasures of Elysium ... Thus, did our connexion go forward in the most delightful manner ...'" (NYT) |

Lady Augusta Campbell

@NPL |

Lover in 1781.

Daughter of John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll & Elizabeth Gunning, 1st Baroness Hamilton of Hameldon

Wife of Brig. Gen. Henry Mordaunt Clavering (1759-1850)

Eloping with her future husband.

" . . . 'Lady Augusta Campbell is married to Mr. Clavering, the youngest son of General Clavering. He being only two-and-twenty, and Lady Augusta being a good many years older, makes people imagine that she rather ran away with him than he with her. They went away from the Duchess of Ancaster's, who saw masks that night. The Duchess of Argyll went home, and thought that Lady Augusta would soon follow her, but after sitting up till five o'clock, and no Lady Augusta returning, she sent in search of her to the Duchess of Ancaster's. No tidings were to be learned there of the fair fugitive. She, it seems, as soon as her mother went home, left the duchess's with Mr. Clavering and went with him to Bicester, in Oxfordshire, where they were married. She, it is said, was married in her domino. Accoutred as she was she plunged in. It is to be hoped she dropped the mask. The lover had been the day before to Cranbourne Alley, and ha procured every kind of female dress necessary for Lady Augusta." (The Life of George the Fourth, Vol 1: 110)

" . . . At this time her name was linked with that of the Prince of Wales, but within a few years, in 1788, as 'a very spirited lady', she eloped with and married Brigadier-General Henry Mordaunt Clavering, a notorious gambler from whom she soon separated. . . ." (Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800)

" . . . Later on there were stories as to the admiration of the Prince of Wales for her [Elizabeth Gunning] eldest daughter, Augusta, who in her early youth had much of her mother's beauty, still she could not, said one who saw them both, be addressed as 'O matre pulchra filia pulchrior.' Her youth, her rank, her face, which was very charming though not intelligent, compensated for the defects of her shape and figure, she possessed, however, neither accomplishments nor mental qualities to retain her Hamlet in lasting bondage; the poor Ophelia had rather a melancholy fate. Harassed by the on dits flying about as to the Prince's sudden coldness, Lady Augusta took a summary way of cutting short all the annoyance she was enduring. She had other admirers ready to avail themselves of her state of mind, and with one of these, Mr. Clavering, she eloped one night from the Duchess of Ancaster's ball. . . ." (Some Celebrated Beauties of the Last Century: 92)

|

Elizabeth Armistead |

Elizabeth Armistead (1750-1842).

Lover in 1781-1782.

English courtesan.

The Prince had a great fondness for Mrs. Armistead.

" . . . A great beauty of cockney origins, Elizabeth Armistead was always known, like Dr. Johnson's Mrs. Thrale, by her surname and title. She had been the mistress of Lord George Cavendish, the brother of the Duke of Devonshire, before being taking on by the Prince of Wales and finally ending up with Fox. Unlike the transient relationships that characterized London society at the time, they [Fox & Elizabeth] were married in 1795 and theirs proved to be a lasting romance, with Mrs. Armistead providing the love and support Fox needed to continue functioning n spire of his wild lifestyle. There is no doubt that the prince looked upon them as two of his closest friends. He had a great fondness for Mrs. Armistead as, unlike his other discarded mistresses, she made no financial demands on him when they parted. Her eventual reward was a pension of 500 pounds a year from Gorge to support her after the death of Fox." (Prinny and His Pals: George IV and the Remarkable Gift of Royal Friendship)

Grace Elliott (1758-1823)

Lover in 1781.

Scottish courtesan, socialite & royal mistress.

Daughter of: Hew Dalrymple (d.1774), Scottish advocate & poet & Grisel Craw (d.1765)

Wife of: John Elliott, 1st Baronet, a very wealthy physician, mar 1771, div 1776.

"During the summer of 1781, possibly in June, Grace had a brief affair with the Prince of Wales. Over in a short time, possibly a matter of weeks, this affair was important because Grace became pregnant. Her daughter was born March 30, 1782, and Grace stated that the father was the Prince of Wales. The child was christened Georgiana Augusta Frederica Elliott for the prince, and the christening record (which still exists) shows the prince as her father. Although the Prince of Wales didn't deny the child, he did not acknowledge her either. However the christening record was left intact, and the prince paid Grace an annuity from at least 1800 until her death. (The annuity may have started earlier-the prince's accounts are not complete.)" (Gilbert)

" . . . Already her successor was in place. Grace Dalrymple Eliot, the courtesan, known as Dally the Tall, had quarreled with her French lover the duc de Chartres and hurried back to England, having heard that greater quarry was free. In 1782 she had a daughter by the Prince, a child he refused to acknowledge. The girl later married into aristocracy." (Madams: Bands and Brothel-Keepers of London)

"She arrived in the English capital just as the heir to the throne, the Prince of Wales, was ending his latest affair of the heart. He looked around for a new love interest and he saw Grace Elliott. Their relationship lasted just a few months at most. Then Grace discovered that she was pregnant. She insisted that the father was the Prince of Wales, but rumors suggested that there were at least four other candidates, including Cholmondeley. The baby, born on March 30, 1782, was christened Georgiana Augusta Frederica Elliott. Cholmondeley agreed to take responsibility for the child, but inevitably there were rumors that he'd done so at the suggestion of the real father, the Prince of Wales. The mystery of Georgiana's father was never resolved. She was brought up with the Cholmondeley children." (Scarlet Women: 68)

Anna Sophia Hodges.

Lover in 1783.

"As already stated, Mrs. Fitzherbert was a cousin of the notorious Mrs. Hodges, who for a brief time in 1783 was mistress of George IV, when Prince of Wales and later Charles Wyndham, brother of Lord Egremont. Mrs Hodges' affairs were so notorious that they brought considerable shame upon the Smythe family but the latter already had several skeletons in the family cupboard. . . ." (Royal Sex: Mistresses & Lovers of the British Royal Family)

"The subject of a notorious 'crim con' case in 1791 when her husband Anthony Hodges sued the Hon. Charles Wyndham after the birth of a daughter, Caroline Wyndham (d. 1876). Mrs. Hodges was said also to have been mistress to the Prince of Wales." (British Museum)

|

Georgiana

Duchess of Devonshire |

Georgiana Spencer, Duchess of Devonshire.

Lover in 1783-1785.

Charlotte Fortescue.

Lover in 1784.

Angelic figure of a sea nymph.

"It was at this time that he manifested that predilection for Brighton which induced him at a future period to make that town his residence. The reports current at the time were that he was more influenced by the angelic figure of a sea nymph he saw upon the beach than by the marine views or the salubrity of the place. In this amour, however, he was completely duped. So far as personal charms were concerned, Charlotte Fortescue was as lovely as one of Tennyson's sea fairies, but in mental qualifications she was very illiterate, and unparalleled in artifice. She knew how to throw such an air of innocent simplicity over her actions that would have deceived even a greater adept than this royal libertine. She was not long in discovering the high rank of the individual whom she had captivated by her charms, and with her innate cunning for a time frustrated all his arrempts to obtain a private interview, knowing that what is easily gained is lightly prized. Keeping her residence secret for some days, she was neither seen nor heard of. Upon a sudden she made her appearance suffused in tears, announced her approaching marriage and her departure from the country. This stirred the Prince to immediate action, and, overcoming all her well feigned scruples, a romantic elopement was arranged, in which the beautiful fugitive should fly with the Prince in the dress of a footman and a post chaise was to be waiting a few miles on the London road to bear away the prize." (The Life of George IV, (King of England): 80)

"The Prince was once outdone by one of his profligate companions, Col. George Hanger, known familiarly as the Knight of the Black Diamond, the wit and satirist of the royal clique. Both men fell for the same attractive, but illiterate, female -- Chalotte Fortescue. Believing she was eloping to London with the Regent (while having been conducgting a relationship with Hanger), she was outwitted by the Colonel dressed as her royal lover. Seated on the coach-box and unrecognized until their arrival, he thus bore his mistress -- herself in the disguise of a footman -- off to the metropolis." (Brighton Crime and Vice, 1800-2000: 78)

Of fine form, but illiterate & ignorant.

"This entrancing being was a girl named Charlotte Fortescue, who although . . . was 'of the first order of fine forms . . . was one of the most illiterate and ignorant of human beings.' However, Charlotte's charms, together with her air of simplicity and innocence, effectively concealed the lack of any more dependable qualities, and soon the Prince had become her abject slave. Making a pretence (sic) of virtue and timidity, she skillfully led the Prince on, carefully avoiding any risk of giving way to his desires, until his passion was almost uncontrollable. . . . " (George IV)

Affair's end & aftermath.

" . . . However, when he discovered that she was carrying on an intrigue at the same time with his friend George Hanger the girl found herself deserted by both, and thus completely failed to achieve that transition from a dull and obscure provincial existence to a life of sophisticated gaiety, which as the Spirit of Brighton in Rex Whistler's painting she eternally symbolises." (George IV)

|

Maria Fitzherbert |

Maria Fitzherbert

(1756-1837)

Lover in 1784-1811

Daughter of William Smythe of Brambridge, Hampshire & Mary Ann Errington of Beaufront, Northumberland.

Wife of:

1) Edward Weld, mar 1775

2) Thomas Fitzherbert (d.1781) mar 1778

3) George, Prince of Wales, mar 1785.

From Grace to Maria to Frances.

"After Grace, the Prince of Wales became enamoured of a Catholic widow named Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert but the lady proved to be not such an easy conquest as Grace. She withstood his charms until he made a morganatic marriage to her, one that was unsanctioned by his father, King George III, and therefore not legal. Having married Mrs. Fitzherbert primarily to bed her, once the object was achieved he soon tired of her and set his sights on the plump and middle-aged Countess of Jersey. A grandmother over the age of 40, Lady Jersey nevertheless captivated him and she ruled the prince's heart for some time thereafter." (A Right Royal Scandal)

The love of his life.

"George loved many women, but Maria Fitzherbert was the love of his life. She was the widow of Thomas Fitzherbert and Edward Weld; she was the grand-daughter of a northern Catholic, Sir John Smythe; and, on 15 December 1785, she probably (secretly) became George IV's wife." (Human Biology and History: 81)

First Encounter.

"The first time that the Prince of Wales saw Mrs. Fitzherbert, was in Lady Sefton's box at the Opera; and the novelty of her face, more that the brilliancy of her charms, had the usual effect of enamouring the Prince. But in this instance he had not to do with a raw inexperienced girl, but with an experienced dame, who had been twice a widow, and who consequently was not likely to surrender upon common terms. She looked forward to a more brilliant prospect which her ambition might artfully suggest, founded upon the feeble character of an amorous young prince; and when his Royal Highness first declared himself her admirer, she gave him not the slightest hope of success, but, in the true spirit of the finished coquette, she turned away from his protestations, and in order to avoid his importunities, quitted the kingdom, and took up her residence at Prombiers, in Lorraine, in France. . . ." (Memoirs of George IV, 1:125)

First encounter -- another version.

"It was in 1783, and on the river at Richmond, that the Prince of Wales first noticed Mrs. Fitzherbert. He fell in love immediately, and was completely unable to conceal his infatuation. Indeed, a few days later he began, after dinner, to bewail the fortune of his birth. What had he done, he asked, that he should be forced, in due course, to marry some 'ugly German frow'? Why could he not be free to do what he liked, as were other men? The Prince's manner betrayed his secret, and Rigby, the Master of the Rolls, to whom the questions apparently were addressed, replied discreetly: 'Faith, sir, I am not yet drunk enough to give advice to the Prince of Wales about marrying.' According to another story, however, George saw his enchantress earlier in the year when she was sitting with Lady Sefton in a box at the Opera, and so greatly was he impressed by her beauty that he followed her home." (Love-Stories Of Famous People. King George IV. And Mrs. Fitzherbert. Part 2)Not a mistress, but his first wife.

"However, mention will be made here of another woman with whom Prince George enjoyed sexual relations, because she was not merely a mistress. She was his first wife, Mary Anne (or Maria) Smythe Fitzherbert (1756-1837), a Roman Catholic, who had previously been twice married and twice widowed. The prince had not intended marriage, but she refused to grant sexual favors without benefit of matrimony, and he relented. Prince George and Mrs. Fitzherbert were married on December 15, 1785. The marriage was declared null and void on account of the provisions of the Royal Marriages Act of 1772. This was a lucky break for Prince George, since he was a man of limited attention span toward specific members of the opposite sex, and surely not prepared to give up a throne for the love of a woman. . . . " (The English Royal Family of America:181)

". . . He married his mistress, Maria Fitzherbert, in secret at her house on Park Street, near Park Lane, on 15 December 1785. It had to be in secret. She was a Catholic and he wouldn't be able to take the throne if the truth emerged. . . Ten years later the prince was pressed into an 'official' marriage with Caroline of Brunswick." (West End Chronicles)

". . . George, however, hankered anew for Maria Fitzherbert, and they lived together again from 1800. From 1807, George's favour for Isabella, Marchioness of Hertford put this relationship under strain and in December 1809 it came to an end." (The Hanoverians: 157)

Physical appearance & personal qualities.

"Maria was not a conventional beauty but she had a flawless complexion offset by an (sic) prominent aquiline nose and a character that radiated a very becoming serenity and gentility accompanied by an air of quiet common sense and sensitivity which attracted all and sundry. She was according to Lady Hester Stanhope 'sweet by nature and who even if they are not washed for a fortnight are free from odour.'." (The Hanoverians: 157)

References for Mrs. Fitzherbert.

History Times History.

Anna Maria Crouch

(1763-1805)

Lover in 1788.

English singer & stage actress.

Wife of: Naval Lieutenant named Crouch mar 1784, sep 1791

"Anna Maria Crouch was a singer and actress well known on the London stage. She was a child performer and sang in the drawing room of Lady Lewes, the wife of the then Lord Mayor of London, going on to appear at Drury Lane Theatre at age 16." (Women of Brighton)

"In 1791, Anna Maria Crouch separated permanently from her husband . By a private agreement, she agrees to pay him an annual pension. But, at the time, she would have briefly become the mistress of the Prince of Wales (assertion that the woman fiercely denied). The prince would have paid him a huge sum after their breakup." (Ann Selina, 'L'Italiana in Londra')

"Michael Kelly was a Dublin-born musician and singer who had been giving performances all over Europe and had also dabbled in acting. He arrived in London from Vienna with Nancy Storace, looking to making it big in England's capital city. A mere three years after her marriage, Anna Maria began an affair with Kelly. The two were not only sleeping together but also acting together, which as we all know, made great whisperings around London. To further delve into infidelity, Mrs. Crouch caught the eye of the Prince of Wales (he always did have a thing for actresses) and she had a brief affair with him. Let us examine how very tartly this was: Anna Maria was married and having an affair, and possibly hadn't cut things off with Kelly yet. The Prince, was also married at this time albeit, illegally to Maria Fitzherbert. Although the affair was brief, Anna Maria still managed to make off with a £10,000 bond from the silly prince, which probably ticked Perdita Robinson off royally because of all trouble she went through to get some of the prince's money!" (Duchess of Devonshire's)

" . . . By the summer of 1788 the relationship [with Mrs. Firzherbert] was beginning to wear thin. Never one to stay faithful to one woman for long, the Prince's eye began to wander and Fox, who was now alienated from Maria, and saw her separation from the Prince as the Whigs' only hope, sought to encourage him. He introduced George to an an opera singer named Anna Maria Crouch, the mistress of Michael Kelly who was also an opera singer and friend of Mozart. The affair lasted only a few days. but it was ominous for the future. . . ." (George IV: 46)

Her other lover:

Michael Kelly.

Lover in 1787

"In 1787 she met a young and talented Irish baritone, Michael Kelly, whom she taught to speak English, to sing and to act. She nurtured his career and eventually he was so successful that he appeared at the Drury Lane Theatre in the London opposite her. They became lovers but this did not stop her having a short but rewarding liaison with the Prince of Wales who gave her a bond for £10,000. It was not a lasting affair and Anna Maria soon returned to her Michael Kelly and they continued to live happily together owning houses in London as well as one at 9 Mulberry Square, North Street in Brighton (now long since demolished; it was on the north side more or less where Premier Lodge is now.)" (Women of Brighton)

|

Elizabeth Billington |

Elizabeth Billington

(1765-1818)

Lover in 1788.

British opera singer.

Daughter of Carl Weichsel, German-born principal oboist at the King's Theater & Frederika Weirman, an English vocalist of some distinction.

Wife of:

1. James Billington, an Irish double bass player.

2. M. Fressinet.

"Elizabeth Billington was also something of a sensation off the stage. A scurrilous biography of her sold out in less than a day. The book contained what were purportedly copies of intimate letters about her famous lovers---including, they say, the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV. In a more dignified celebration of her fame, after she recovered from a six-week-long illness on her Italian tour, the opera house in Venice was illuminated for three days." (Fifty Inventions That Shaped the Modern Economy: 15)

|

Laetitia, Lady Lade

RCT |

Laetitia Derby

Lady Lade

(d.1825).

Lover in 1780s.

Wife of Sir John Lade, 2nd Baronet.

"To the indelible reproach of the female character, be it said, that, in the ruin of this lovely girl, a woman was the principal agent; and when we mention the name of Lady Lade, we have given the synonyma for all that was vile and despicable in woman. This notorious female first beheld the light in Lukner's lane, St. Giles', from which she emerged, on account of the fineness of her person, to become the mistress of John Rann, who forfeited his life on the scaffold at Tyburn, and, after passing through several gradations, she was taken under the protection of the Duke of York. We, therefore, now behold her in her own box at the opera, splendidly arrayed, her whole ambition gratified in viewing lords, dukes, and the princes of the blood at her side, paying that homage which only superior virtue and attractive manners ought to exact. But it was in the Windsor hunt that this lady first attracted the notice of the Prince. She was then the wife of Sir John Lade, and to be well up with the hounds---to be in at the death---to drive a phaeton four in hand, and to evince a perfect knowledge of all technical phrases of coachmanship, not an individual in the whole hunt could compete with Lady Lade; nor was she excelled by even Sir John himself, who was the tutor of the Prince in the art of driving, and from whom he received a pension, for his services, of 400 pounds per annum." (The Life of George IV, (King of England): 151)

" . . . Sir John Lade was a famous driver and encouraged the Prince to attempt daredevil exploits with his phaeton. . . Lady Lade, formerly known as Mrs. Smith, who may have been for a time one of the Prince's mistresses, was equally rackety. Her first husband had been a highwayman and was hanged for it. George later granted her a pension of 300 pounds. . . ." (George IV: 15)

"Letitia (Letty) Lade nee Derby was likely a member of the Drury Lane working class before rising to tonnish circles. Some sources suggest her father was a sedan chair operator and that she herself was a cook at a brothel. Rumored to be the mistress (or Free Love Consort) of highwayman “Sixteen String Jack” Rann (who was executed in 1774) and later the mistress of the Duke of York, she eventually caught the eye of Prinny. According to a 1894 source: 'a skilled horsewoman…(she) regularly attended th Windsor hunt. It was at one of these meetings that she attracted the attention of the Prince of Wales by her bold riding.'" (Regency Reader)

" . . . Laetitia, Lady Lade, was the wife of Sir John Lade. She was a notorious adventuress and renowned as a skilled rider. Her reputation for using bad language made her unpopular among the fashionable ladies at court, but she and her husband were both friends of the Prince of Wales. She is here shown mounted at full-length on a rearing bay horse in profile to the left, wearing a blue riding habit with a charcoal grey plumed top hat; a tree trunk to the right, the branches of which occupy the entire top of the canvas; park and pond beyond." (Royal Collection Trust)

"I imagine the marriage was actually a fun one. The two were so similar in their tastes. When John's friend, the Prince took interest in Letitia, the two seemed to enjoy the game of his pursuit (The Prince even commissioned Stubbs to paint her portrait). Unfortunately, they also had similar spending habits and were commonly in financial turmoil. Letitia relished her new place among the aristocracy while they, in turn, found her a bit course. Her casual cursing was overwhelming to many and began the phrase, "he swears like Letty Lade!" Her carnal past also was a hot topic and she was said to, "withstand the fiercest assault and renew the charge with renovated ardour, even when her victim sinks dropping and crestfallen before her," and that she never "turned her back against the most vigorous assailant.'" (The Duchess of Devonshire's)

Perfect target for a social climber's husband.

"Climbing the social ladder proved to work out well for Letitia. Her connections with the Duke helped her form even more. Soon she was modeling for Reynolds under the name of "Mrs. Smith," the portrait of which was exhibited at the 1785 Royal Academy exhibition. Knowing that a son of the king would eventually tire of her, Letitia began to set her sights on his (and Rann's) friend, the Baronet, Sir John Lade. John was rich, fun, good looking, and friends with the Prince of Wales so he was the perfect target for Letitia. He was was a true horseman, one of the best riders and drivers at the time. He was so into it, that he was constantly wearing his riding gear and even insisted on carrying a whip on his person all the time. No wonder Letitia was interested! She won John over with her own natural horsemanship. Here was a beautiful, vivacious, and slightly dangerous woman who shared his love of the sport. Perhaps he could hone her riding skills and maybe even tame her as well? Their affair lasted quite a while and was scoffed at by his family before John made Letitia "Derby" a honest woman, when he married her in 1787." (The Duchess of Devonshire's)

Lady Lade's other lovers were:

1. Frederick of Great Britain, Duke of York (Lover in 1774)

2. Jack Rann.

Elizabeth Harrington.

Lover in c1790.

First Encounter.

"It was in the company of this woman [Lady Lade], that the Prince of Wales, one day returning from the chace (sic), met the beautiful Elizabeth Harrington walking on the Richmond road, in the company of her parents. She was immediately marked out as a new victim to his libidinous desires, and Lady Lade undertook to effect the introduction. It was under the pretence of sudden disposition that this female panderer broke into the sanctuary of domestic happiness, and with so much difficulty was the task accompanied which she had to accomplish that she at one time relinquished it, despairing of success. But the Prince had seen the luscious fruit, and to retire without the enjoyment of it was at variance with his usual mode of action. He goaded on his emissary---he threw to the winds his vows of constancy and 'unalterable love' which he had sworn at the alter to HIS WIFE, and, like Caesar of old, though on a far different occasion, he determined to realize the words veni, vidi, vici." (Memoirs of George the Fourth, 1: 142)

|

Dorothy Jordan

@NPG |

(1761-1816)

Lover in 1791-1811.

Irish actress, courtesan & royal mistress

Daughter of Francis Bland and his mistress Grace Phillips (a.k.a. Mrs. Frances)

Dorothy's other lovers:

1. Richard Daly, Manager of Theatre Royal, Cork, lover in 1780

2. Charles Foyne, an Army lieutenant

3. Tate Wilkinson, theatre manager, lover in 1782-1785

4. George Inchbald, actor

5, Sir Richard Ford, a police magistrate & lawyer.

6. Duke of Clarence (later William IV), lover in 1791.

Dorothy's personal & family background.

"Mrs. Jordan was another of the players whose youth belonged to the last century, but who did not retire till after Edmund Kean had given new life to the stage. She came of a lively mother, who was one of the many olive branches of a poor Welsh clergyman, from whose humble home she more undutifully than unnaturally eloped with, and married, a gallant Captain named Bland. The new home was set up in Waterford, where Dorothy Bland was born in 1762; and nine children were there living when the Captain's friends procured the annulling of the marriage, and caused the hearth to become desolate. Dorothy was the most self-reliant of the family, for at an early age she made her way to Dublin, and under the name of Miss Francis, played everything, from sprightly girls to tragedy queens. As she produced little or no effect, she crossed the Channel to Tate Wilkinson, who inquired what she played,---tragedy, comedy, high or low, opera or farce? . . ." (Their Majesties' Servants, Volume 3: 312)

"Dorothea Jordan's mother was an actress from Wales who married a young Irish army captain by the name of Bland. The young couple were married in Ireland by a Catholic priest but, because they were both minors, Bland's father objected to the match and was able to have the marriage annulled. . . ." (Wild Irish Women: 67)

"In 1791 Dorothy yielded to William's ardent suit for---it was reported in the papers---the princely sum of three thousand pounds before consummation and one thousand pounds a year. Together with her theatrical earnings, this would have made Dorothy a wealthy woman. But kindhearted Dorothy and her money soon parted ways." (Sex with Kings: 151)

Affair's end & aftermath.

"The Duke of Clarence’s relationship with Mrs Jordan ended in 1811. Mrs Jordan was paid a handsome financial settlement and kept custody of her daughters under the condition she did not resume her stage work. She did however, resume her work as an actress to help pay of some debts of one of her son-in-laws (husband to one of her daughters prior to her relationship with William). This resulted in losing her payments from the Duke of Clarence. She retired to Paris and died in poverty in 1816." (European Royal History)

|

Frances Villiers

Countess of Jersey

|

Frances Villiers

Countess of Jersey

(1753-1821).

Lover in 1794-1796.

Daughter of Rev. Dr. Philip Twysden, Bishop of Raphoe & Frances Carter

Wife of George Villiers, 4th Earl of Jersey, 7th Viscount Grandison, Viscount Dartford & Baron of Hoo; Lord of the Bedchamber & Master of Horse of the Prince of Wales, mar 1770.

"Queen Charlotte, worried by the whole situation, enlisted the aid of two of her ladies-in-waiting, Lady Hertford and Lady Jersey, to lure the foolish heir to the throne away from Mrs; Fitzherbert. Initially the motherly Lady Hertford failed to make an impression. It was Lady Frances Jersey, razor-slim, clever as a serpent and bored by her elderly husband, who managed to lure the young Prince of Wales into her bed. Keen to win the Queen's approval and gain influence over the Prince of Wales, the future King, Lady Jersey did her best to turn Prinny against Mrs. Fitzherbert. Telling him that Maria was fat had no effect---clearly the Prince liked his beloved Fitz as she was." (Royal Mistresses of the House of Hanover-Windsor)

The most hated woman in the country.

"Fanny Twysden, the future Countess of Jersey, was one of the great beauties of her time. Clever and witty, she had enormous charm. She was a leader of Society, in its grandest sense, and a woman of 'irresistible seduction and fascination'. She was also unprincipled and malevolent and was destined to become the most hated woman in the country, burned in effigy and her carriage pelted by the mob." (The Countess: The Scandalous Life of Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey)

"Fanny Twysden grew to be a young lady of great charm and accomplishment. She was spirited and vivacious with considerable social skills. She was an accomplished musician and, though small, was 'exceedingly pretty and fascinating' -- as well as inheriting her father's love of hunting. In future years, she was described by Queen Charlotte as Lord Jersey's 'bewitching little wife' and it is said that, 'In her youth, Frances Twysden had been famous throughout all Ireland for her beauty.'" (The Countess)

"Frances, Lady Jersey was forty-one and a grandmother when she became the Prince of Wales's mistress. She was a friend of his mother's and had known him for years. An attractive, clever woman with an acerbic tongue and ambitions of acquiring royal influence, she deliberately set out to capture the Prince and ruthlessly encouraged him to cast off his morganatic wife, Maria Fitzherbert, in favour of herself. . . In 1796, after the birth of his daughter, the Prince tired of Lady Jersey and ended the relationship." (Georgette Heyer's Regency World: 301)

"Then, as a grandmother several times over, she ousted Mrs Fitzherbert as mistress to the Prince of Wales, separating a foolish Prince from his wiser friends and ruling his life.

Rejoicing in her role at the pinnacle of society, she alienated many as she lorded over it. With the Prince putty in her hands she arranged his disastrous marriage to his lumpen cousin Princess Caroline of Brunswick to consolidate her position. Her cruelty to Caroline, and the wave of scandals that followed, enraged the country, threatened the monarchy itself and blackened the reputation of the Prince for posterity." (The wicked Countess of Jersey who became mistress to George IV)

". . . (H)e [George IV] had also fallen under the baleful influence of Lady Jersey. At forty-one she was still a beautiful and captivating woman, even after bearing nine children. The Prince had always looked on her with a keen eye, and she, seeing that a vacancy was about to open up, manoeuvred herself into position. She was insufferable, making it a point to be as vicious as possible to any woman who had once been connected with the Prince. She was vile to Mrs. Fitzherbert and sneering towards Georgiana and Lady Melbourne. There could be no real reconciliation between the Prince and Georgiana as long as Lady Jersey remained his mistress." (The Duchess: 281)

Lady Jersey's spouse & offspring.

"Frances, daughter of the Rev. Philip Twysden, and wife of George Bussy Villiers, fourth Earl of Jersey, who died in 1805. He had been Master of the Horse in the Prince's household, and she was the Prince's mistress at the time of his marriage. They finally parted in 1798." (The Letters of King George IV, Volumes 2-3: 216)

"Despite causing her children great pain Frances loved them all dearly and was proud of them, whoever their fathers. Her daughters were all great beauties and she campaigned hard to win them good marriages. Regardless of her reputation (some called her “Satan’s representative on earth”) and much resistance she succeeded – a duke’s brother, a Jamaican sugar baron, the heir to an earldom (and a hero at Waterloo), and the richest commoner in the country. A fifth married “the most beautiful man in England” (but only after the Countess brought her own affair with him to an end), and her elder son married for love – his wife just happened to be a great beauty with enormous wealth." (The wicked Countess of Jersey who became mistress to George IV)

Affair's end & aftermath.

"Despite her Machiavellian wiles, Lady Jersey's reign over the prince's heart and household came to an abrupt end when he moved on from her to another matronly grandmother, the Marchioness of Hertford. The British public began to make clear their feelings regarding the prince's profligacy and his attitude towards his wife, and he was publicly satirized and mocked, both for his appearance and his behaviour." (A Right Royal Scandal: 10)

Lady Jersey's other lovers were:

1. William Augustus Fawkener.

Privy Council Clerk.

Lover in 1773.

"William Fawkener was certainly to play a significant part in Frances Jersey's life. He was the elder son of Sir Everard Fawkener, former Ambassador to the Porte and Secretary to the Duke of Cumberland, after whom William appears to have been named. . . William's mother was the natural daughter of General Charles Churchill, brother of the great Duke of Marlborough. His sisters were Mrs. Crewe, 'the fashionable beauty, whose mind kept the promise . . . made by her face . . . the woman who ][Fox] said he preferred to any living . . .' and the celebrated Mrs. Bouverie, herself a great beauty." (The Countess: The Scandalous Life of Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey)

2. Frederick Howard, 5th Earl of Carlisle

3. Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, 8th Duke of Hamilton

4. William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire.

Lover in 1778.

|

Sarah Sophia Fane

Countess of Jersey

@Wikipedia |

(1785-1867)

Lover in 1794-1798.

Daughter of John, 10th Earl of Westmorland & Sarah Anne, daughter/sole heiress of Robert Child of Osterley Park.

Wife of: George Villiers, 5th Earl of Jersey & 8th Viscount Grandison. mar 1804.

Honours & achievements.

"Sarah, Lady Jersey . . . became a leader of the best of London society; she was a patroness of Almack's Assembly Rooms. . . She is reported to have introduced the quadrille to Almack's in 1815. She was immortalized as Zenobia in Disraeli's Endymion. . . . " (History Home)

Love Life: "Royal mistresses were often upper-class married women. The Prince of Wales in the late eighteenth century worked his way through Lady Augusta Campbell, Harriet Vernon, Lady Melbourne, the Duchess of Devonshire and the actress Mrs. Robinson, before he reached the age of 21. Later he went on to Mrs. Armistead, Mrs. Billington, Mrs. Crouch, then Mrs. Fitzherbert whom he married (illegally). Lady Jersey succeeded Mrs. Fitzherbert, then came the Prince's legal marriage (after which Lady Jersey still acted as his mistress, until he returned to Mrs. Fitzherbert for a time). Lady Hertford succeeded Mrs. Fitzherbert, and she in turn was supplanted by Lady Conyngham, who was known as the Vice-queen when the Prince became George IV, and who survived as mistress until the King's death. All these women sailed around in glory as long as they were favourites; they had great power and were very proud of their situation; they collected money and jewellery, found jobs for heir friends and relations, and married off their children and relatives advantageously...." (Perkin, 2002, p. 92)

Eliza Fox (1770-1840)

Lover in 1798-1799.

Daughter of Joseph, a tavern keeper, & Eleanor Fox.

Eliza's personal & family background.

"George Seymour Crole, was born 23 August 1799 in Chelsea, the illegitimate son of George, Prince of Wales, later George IV, and Elizabeth Fox, alias Crole. He was never officially recognised by his father, although there is evidence to show that he admitted to it privately, but he was provided for throughout his life by his father as well as George William IV and Queen Victoria. George's mother had been born 1770, the daughter of Joseph and Eleanor Fox. Joseph had been a tavern keeper in Bow St., Covent Garden before acquiring the lease of the Brighton theatre, and was described by one contemporary as 'a very odd character . . . he could combine twenty occupations without being clever in one. . . He was actor, fiddler, painter etc.' and by another as 'a low person at Brighthelmstone'." (Royal Bastards: Illegitimate Children of the British Royal Family)

"Young Crole's date o of birth suggests that Elizabeth's relationship with the Prince of Wales began in late 1798, although there is evidence to suggest that it may have begun earlier in the year. Egremont had settled on her an annuity of 400 ponds per annum, whereas the Prince promised her an annuity of 1,000 pounds plus a house in Pall Mall. Sadly neither materialized and Elizabeth was forced to remain at Hans Place. However, she did eventually receive an annuity of 500 pounds from the Privy Purse which was paid to her for th rest of her life." (Royal Bastards)

Natural offspring.

George Seymour Crole (1799-1863).

"Whether or not George had children by Maria Fitzherbert, there can be little doubt than other liaisons during his life must have been productive. The most probably candidate is George Seymour Crole, born in 1799 to Elizabeth Fox who was the mistress of Lord Egremont at Petworth and who was also mistress for a time of the Prince of Wales. She was the daughter of the manager of the Brighton theatre and later of two other theatres which he built himself. . . He died in debt in 1791 leaving his daughter in the care of Lord Egremont, who fathered four children born to her. She adopted the surname Crole and became George's temporary mistress during the period after his separation from Caroline. Their son was born on 23 August 1799 but the relationship with George ended when he was reunited with Maria the following year. He did not forget Elizabeth, but ensured that she would be looked after by Egremont and settled a pension of 500 pounds from the Privy Purse on her for the rest of her life. Her son was discreetly looked after his fees at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst were paid from the same source and in 1817 a commission in the 21st Dragoons was purchased for him. . . ." (George IV: 291)

". . . Lady Jersey had lost George's favour in 1798, although she was swiftly replaced by Elizabeth Fox, the mistress of Lord Egremont. By George, Elizabeth Fox had a son, George Crole, who received 10,000 pounds and an annuity of 300 pounds after George's death. . . ." (The Hanoverians:157)

Mary Anne Nash (d.1851)

Lover in in 1800.

"On Decemebr 17, 1798, his first wife having died, Nash married Mary Anne Bradley, the daughter of a coal merchant. This marriage seems to have been more felicitous for Nash. He and Mary Anne socialized easily and frequently entertained his professional friends at home. The couple would have no children, but a wide circle of friends and relatives would remain devoted to them throughout their lives. At the time of this marriage, Nash also purchased land at East Cowes on the Isle of Eight; there he would build for himself a small but comfortable Gothic-style country home near the sea. In addition, he and his wife maintained a Mondon home during his active years as an architect." (The 17th and 18th Centuries: Dictionary of World Biography, Volume 4, Volume 4: 1013)

"In 1798 the 46 year-old Nash mysteriously became very wealthy at the same time as he married the relatively poor but beautiful 24 year-old Mary Anne Bradley. Nash acknowledged no children but Mary Anne acquired five mysterious infants, officially distant relatives with the family name of Pennethorne, born from the time of the marriage up to 1808. They were widely assumed to be among the Prince’s many illegitimate children." (Isle of Wight Beacon)

"Regardless, Nash's household and way of life demonstrated inexplicable affluence from 1798 on, and he did become the prince's favorite architect. After her husband's death in 1835, Mar Ann Nash moved permanently to Hamsptead, where she lived with her daughter, Anne, until her own death in 1851." (By the King's Design)

|

| Harriette Wilson |

Harriette Wilson. (1786-1846)

Lover in 1801.

"Harriette Wilson, the celebrated courtesan, was the daughter of John Dubochet, a clockmaker in Mayfair. Her Memoirs, published in paper cover parts in 1825 . . . went through over thirty editions in one year, and so great was the demand that a barrier had to be erected to regulate the crowd which surged round Stockdale's shop.. . . In the first volume she describes how she offered herself to George IV when he was Prince of wales, who replied, through Colonel Thomas: 'Miss Wilson's letter has been received by the noble individual to whom it was addressed. If Miss Wilson will come to town, she may have an interview, by directing her letter as before.'" (The Letters of King George IV, 1812-1830, Volume 3: 178)

Olga Alexandrovna Zherebzova

(1766-1849)

Lover in 1801?.

Russian aristocrat.

Daughter of Alexander Nikolaevich Zubov & Elizaveta Vasilyevna Voronova.

Wife of: Aleksander Zheretzov.

Olga Zherebtsova was the sister of Prince Platon Zubov, a handsome young man who became one of Catherine the Great’s court ‘favourites’ in the early 1790s. After their family fell from favour following the Empress’s death in 1796, Olga and another of her brothers, Nicholas Zubov, were implicated in the assassination of Catherine’s son, Emperor Paul I, in 1801." (Masterpieces from the Hermitage)

" . . . In England, Olga became the mistress of the Prince Regent, the future King George IV, She gave birth to his son, who was named George Nord." (Rusartnet)

" . . . The most flamboyant was Platon Zubov's elder sister, Olga Zherebtsova, who became a legend in her own right as a former lover of the British ambassador Charles Whitworth, an alleged lynchpin in the conspiracy to assassinate Tsar Paul. Steeped as deeply as her heroine in the works of the French philosophes, Zherebtsova struck Herzen, who met her in her seventies, as 'a strange, eccentric ruin of another age, surrounded by degenerate successors that had sprung up on the mean and barren soil of Petersburg court life.' . . ." (Catherine the Great: 322)

Madame Zherebzova's other lover was:

Charles Whitworth, 1st Earl Whitworth.

"Olga Zherebtsova was the sister of Prince Platon Zubov, the last favourite of Catherine the Great. After the empress died and was succeeded by her son Paul I (1796), Zubov and his brothers hatched a conspiracy to assassinate the new emperor. The plot was financed by the British ambassador, Sir Charles Whitworth, who was also Olga's lover. Paul broke off diplomatic relations with Britain and ordered Whitworth to leave the country (1800). . . ." (rusartnet)

|

Isabella Seymour-Conway

Marchioness of Hertford |

Isabella Seymour-Conway.

Marchioness of Hertford

(1755-1834)

Lover in 1807-1819

(When he was Prince of Wales)

British aristocrat, courtier & royal mistress

Daughter of Charles Ingram, 9th Viscount of Irvine & Frances Shepheard

Wife of: Francis Seymour-Conway, 2nd Marquess of Hertford 1794 (1743-1822)

mar 1776. Vice-Chamberlain of the Royal Household 1812-21.

"Although Prinny had known Lady Isabella for years as the mother of his friend, he now developed a veritable obsession with her. Through his friendship with Lord Yarmouth, the Prince knew when Lady Isabella's husband was away from home. He visited her at Hertford House and Ragley Hall and they would talk about his art collection and possible new purchases." (Royal Mistresses of the House of Hanover-Windsor)

"One of the Prince's most enduring mistresses, Lady Hertford began her relationship with the heir to the throne in 1807 when she was forty-six and he was still Prince of Wales. The affair continued until 1819 when he transferred his affections to Elizabeth, Countess Conyngham. Lady Hertford was a tall, elegant and attractive woman, whose husband was a wealthy Tory peer. She was disliked by some among the ton, including Mrs. Dauntry in Frederica who thought her an 'odious woman' and worried that in the event of Queen Charlotte's death the Regent might allow his mistress to play host at the Drawing-rooms. The Regent was also good friends with Lady Hertford's rake-hell son, Lord Yarmouth." (Georgette Heyer's Regency World: 300)