|

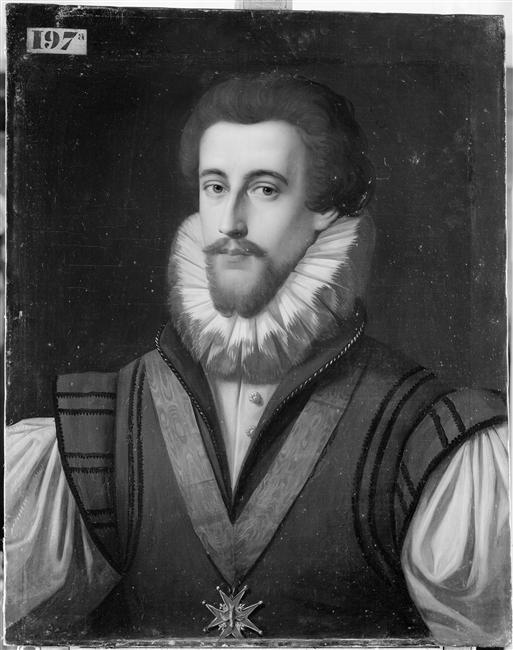

| Henry IV of France @Wikipedia |

(1553-1610)

Son of: Antoine I de Navarre & Jeanne III de Navarre.

1. Marguerite de Valois, Reine de France (1553-1615)

Daughter of Henri II de France & Marie de' Medici.

2. Marie de' Medici. mar 1600.

" . . . Although not classically beautiful, Maria was young and attractive. Her eyes flashed with intelligence, her hair was as golden as her dowry rich, and her alabaster skin glowed like Chinese porcelain. Such a bride should have been sufficiently alluring to pique of a middle-aged king." (Young. Apples of Gold in Settings of Silver: Stories of Dinner as a Work of Art: 66)

Henri IV's unique place in the long history of France.

"In the long history of France, Henri IV has a unique place. It has been said that he was 'the only king whose memory was cherished by the people.' His subjects remembered him as Henri le Grand, Henri the Great. In physical terms he (like Champlain) was not a large man. But there was a greatness in his acts and thoughts, a largeness in his energy and resolve, and an astonishing amplitude in both his virtues and his vices. . . The character of Henri IV appeared in the nicknames that his subjects invented for him. They celebrated him as le roi de coeur, the king of hearts. Others called him le passionne, the passionate one; or le roi libre, the free king. The literati liked to write of him as le vert-galant, the green gallant---vert with its ambiguous connotations of youth, energy,and (in French) promiscuous sexuality; galant in in its mixed association with courtesy and inconstancy. These sobriquets referred to Henri's public and private life. In his many love affairs Henri IV was indeed le roi de coeur, le roi passionne, and le roi libre all at once, in a sense that had nothing to do with political theory or public policy. At the same time, Henri's nicknames also described a unique style of kingship that flowed from the heart. Other monarchs cultivated a distance between themselves and their subjects. They used remoteness as an instrument of royal power. Henri went another way. He was known to leave his palace incognito, and mix with his subjects in informal ways. As a leader he was open, informal, warm, free-spirited, brave, witty, clever, generous to friends and enemies alike. He was also thought to be merciful, fickle, unreliable, and untrustworthy. Another nickname, borrowed from his father, was 'Henri l'ondoyant,' Henri the Unsteady. His best friends acknowledged his flaws, but his warmth and magnetism drew even his enemies to his service." (Champlain's Dream: 47)

Henri IV's personal & family background.

"The young prince's father, Antoine de Bourbon, came from one of the great noble families of France. He was a brave soldier, but some described him with the same word that others would later use for his son: ondoyant, unsteady, unreliable. Henri's mother, Jeanne d'Albret, was made of sterner stuff. She was handsome, headstrong, smart, tough, and extraordinarily able. As heiress to the kingdom of Navarre and the county of Bearn, she held great power in her hands, and she used it to great effect." (Champlain's Dream: 48)

Henri IV's personality and character.

". . . Navarre [Henri IV] . . . had been brought up in a rustic court with a rather austere Protestant sensibility; he was 'neither fastidious in his person nor circumspect in his habits.' His clothes were often worn and dirty, and rarely bathed. As the historian R.J. Knecht baldly noted, 'He reputedly stank like carrion.' Navarre's sexual exploits became legendary, and his appetite indiscriminate. . . . " (Wellman: 228)

More than 50 known sexual partners.

"Although it is uncommon for a man, especially a king, to be pilloried for his sexual adventures, Henry was far more indiscriminate than usual. Those who have tried to track his sexual liaisons have recorded more than fifty known sexual partners. His later popularity and the pens of Bourbon historians meant that his sexual adventures did not detract from his reputation. To some degree they added to his allure as a virile alternative to the last Valois kings, who were perceived as effeminate and degenerate. It is still somewhat surprising that so little opprobrium attaches to Henry's behavior, especially since, on occasion, he neglected his political interests to pursue his passions." (Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France)

Good King Henry.

". . . Henry's reputation, like Gabrielle's, was to some degree redeemed or at least spared by his unexpected and early death. His contemporaries appreciated his reign as having ended civil war, won peace with Spain, and promulgated the Edict of Nantes. Their appreciation shaped the 'Good King Henry' legend which eulogized him as a man of the people---a king of largess and humanity who brought peace and the beginning of prosperity before his reign was tragically cut short---certainly no small accomplishments. his Bourbon descendants built on his positive reputation to assert the value of monarchy. They did not treat his sexual peccadilloes, except as they reinforced his masculinity. . . ." (Queens & Mistresses of Renaissance France:n.d.)

Henry the Celebrity.

" . . . The character of Henri IV appeared in the nicknames that his subjects invented for him. They celebrated him as le roi de coeur, the king of hearts. Others called him le passionne, the passionate one; or le roi libre, the free king. The literati like to write of him as le vert-galant, the green gallant---vert with its ambiguous connotations of youth, energy, and (in French) promiscuous sexuality; galant in its mixed association with courtesy and inconstancy. These sobriquets referred to Henri' public and private life. In his many love affairs Henri IV was indeed le roi de coeur, le roi passionne and le roi libre all at once, in a sense that had nothing to do with political theory or public policy. . . . " (Fischer: 478)

Bassompierre's revelations & reflections about King Henri's amorous life.

"It does undoubtedly appear very strange to our contemplation that the most civilized nation of Europe should have been, for so many centuries, made the footstool of a race so generally corrupt as the house of Bourbon. Some few exceptions there were indeed in this long line of kings, whose names are still honoured, and justly honoured, for the benefits which they have conferred upon mankind both by their example and their precepts. He who was particularly distinguished by the title of St. Louis, according to all the testimony of history well deserved that distinction. He was faithful to his word, attentive to the interests of his subjects, a sincere and zealous observer of all the charities of his private life, and of all the duties of religion. When we come to compare the character of such a man as this with the much vaunted character of Henry IV, whose prowess in war, and whose magnificence in peace, are the perpetual theme of history and song in France, we find that the claims of the latter are but the tinkle of the cymbal, a loud but an empty sound, scarcely worthy of reaching the ear. In truth, it would appear, we apprehend, upon a full investigation, that Henri Quatre was not a whit better that the infamous Regent Orleans, or the debauched and voluptuous Louis XV. . . ." (The Monthly Review: 292)

France's Don Giovanni.

" . . . The list of his mistresses (Italics supplied) is almost as long as that of Don Giovanni himself:--- Henry married, in 1572, Marguerite de Valois, sister of the King of France; which did not prevent him from having for mistresses the Greek Dayelle, and Charlotte de Beaune de Samblancai, wife of Simon de Fizes, Baron de Sauves, both maids of honour of Catherine de Medicis, whom that queen, in 1578, according to her usual line of policy, brought into Gascony to seduce the King of Navarre. He had also many other mistresses of divers conditions; such were the demoiselles Tignonville, de Montaigu, and 'l'Arnaudine, Catherine de Luc, demoiselles d'Agen, Fleurette, daughter of the gardener of the Chateau de Nerac; the demoiselle Rebours, and Francoise de Montmorency, maids of honour to the Queen his wife; he had also, while he was in Gascony, another demoiselle called the Leclain. Bassompierre thus continues the list of mistresses of Henry IV: After his marriage (with Marguerite de Valois) he fell in love with madame de Narmoustier. After that, being at Pau, he was smitten with the widow of the count de Grammont, named the countess de la Guiche; and the desire of seeing her again made him lose all the advantages which he might have drawn from gaining the battle of Coutras. During that passion he came to the crown; and having seen, in passing, the countess de la Roche-Guyon (marchioness of Guercheville) he fell in love with her; and, in order to go to see her, he made foolish and hazardous journeys, in which he was very near being taken by his enemies. This lady was one of those to whim this prince paid his addresses, who had the honour to resist him; she said to him, 'I am too poor to be your wife, and of too good a family to be your mistress.' Having seen Gabrielle d'Estree,' continues Bassompierre, 'he became so enamoured of her that he forgot the countess de la Roche-Guyon. Soon after the death of Gabrielle, Henry took another mistress, Henriette de Balzac d'Entragues. The favours of this lady had cost him, according to the Economies Royales of Sully, a hundred thousand crowns; she further extorted from him a promise of marriage, which Sully had the courage to tear to pieces in presence of the king himself. In 1599, Henry succeeded in dissolving his marriage with Marguerite de Valois, who consented to the divorce; and in 1600 he espoused Mary de Medici. Although provided with this new wife, he continued his old habits. He became enamoured, but without success, of the duchess de Nevers; he was more fortunate with the demoiselle la Bourdaisiere, whom he quitted for an attachment to the wife of a counsellor named Quelin. He then loved, without success, the wife of the master of requests, Boinville. The countess de Limous was less severe. He contracted a more lasting liaison with Jacqueline de Breuil, whom he created countess de Moret. Presently, however, he sought to console himself for infidelities in the affections of the demoiselle des Essarts, whom he created countess de Romorantin, and by whom he had two daughters legitimated. This woman, after the example of the countess de Moret, was guilty of several infidelities towards the king, particularly with Louis de Lorraine, cardinal and archbishop of Rheims. Henry IV had also for his mistress a lady of honour of the queen his wife, called Foulebon. At last he came desperately enamoured of the princesse de Conde, and this was his last love." (The Monthly Review: 293)

Passing from love to love.

" . . . With great facility he passed from love to love---La Petite Tignonville, Mlle. de Montagu, Arnaudine, La Garce (the Wench), Catherine de Luc, Anne de Cambefort. He molted creeds and mistresses without distressing his conscience or shifting his aim." (The Age of Reason Begins: 356)

Bestowing his wayward Heart on factual or fictional amourettes?.

"Careless in regard to himself, Henri did not seek refinements in those on whom, en passant, he bestowed his wayward heart. The anecdotiers and popular tradition ascribe to him at this period of his life many amourettes in which the damsel of his choice was of lowly birth and habits. There were, inter alia, we are told, Arnaudine of Agen; Fleurette, the daughter of the palace gardener at Nerac; a certain Demoiselle Maroquin; Xaintes, his wife's femme-de-chambre; and Picotine Pancoussaire, otherwise the Boulangere de St. Jean: in addition to all the ladies of the Court whom he honoured with his glances. But, except in one or two instances, such as that of Xaintes, those early love affairs remain vague, shadowy, authenticated only by the few passing allusions of memoir-writers and anecdotiers, and---in regard to details---transmitted to us only by popular report in the form of stories, such as merry fellows have told at evening by the fireside in some snug inn or tavern, when a bleak wind from the Pyrenees has been sweeping across the valleys of Bearn. Handed down in this wise from father to son, embellished from time to time just like so many Church legends, those tales undoubtedly testify to the virile reputation which the most amorous of Kings left behind him, but it is difficult to say whether they are even in the smallest degree founded upon fact. As with Queen Marguerite, so has it been with Henri. If one were to believe some accounts, she became the mistress of every man with whom she ever had the slightest intercourse; and in like way one might believe that Henri became the favoured lover of every woman, were the she grande dame, bourgeoisie, servant girl, or country wench, at whom he ever glanced or smiled, with whom he ever jested, or whom, perchance, he chuckled under the chin and gaily kissed as he rode through some village on his way to battle and victory." (Favourites of Henry of Navarre: 54)

Henri IV's amorous adventures with his first mistresses.

"Agrippa d'Aubigne, who in his Histoire Universelle depuis 1550 jusqu'en en 1601, does not disdain to relate in detail some of the amorous adventures of the King of Navarre, and reviews, in the Confession de Sancy, the first mistresses of this Prince, obscure ones or of low degree, who enjoyed but an ephemeral reign and who were frequently ill-paid. He commences by revealing the 'infamous amours' of Bearnais with Catherine de Luc of Agen, 'who afterward died of hunger, she and an infant which she had by the King;' he then goes on to speak of the demoiselle of Mantaigu (daughter of Jean de Balzac, superintendent of the household of the Prince de Conde), whom the chevalier of Mont Luc had left to the mercy of the Prince of Navarre through the mediation of a gentleman of Gascony, named Salbeuf, 'at which he was put to much pain,' for the reason that the poor demoiselle was greatly taken with the chevalier of Mont Luc, whom she had followed all the way to Rome, and for the reason that she felt a profound aversion to the King, 'then full of . . . . contracted by sleeping with Arnaudine, lass of the huntsman Labrosse.' D'Aubigne later names 'the little Tignonville, who was impressionable before being married.' She was the daughter of the governess of the Princess of Navarre, sister of the young Henry; the latter became foolishly enamoured of her, and his passion only grew with the resistance which it encountered. Sully reports, in his Oeconomies Royales, that, about 1576, the Prince went to Bearn, under pretext of seeing a sister, but no one at court was ignorant of the fact that the object of his voyage was to meet with the young Tignonville, 'of whom he was then amorous.' He wished to employ d'Aubigne to 'pimp that pretty creature' (maquinonner cette belle farouche); d'Aubigne refused to undertake such a task, and the Prince was forced to look elsewhere to achieve his end. Tignonville was obstinate and would hear nothing, before being provided with a husband, who would take upon his own shoulders the burden of the adventure; the Prince of Navarre finally married her off and obtained the right of prelibration.The Prince did not blush to descend even to chambermaids and girls of the servants' quarters. He had contracted a venereal malady, in forgetting himself in a stable of Agen, with a concubine of a palfrey, and barely was he cured when he slipped one night into the chamber of a servant maid whose affections he shared with a valet named Goliath; this goujat did not suspect that he had for rival the King his master, and endeavored to kill the latter by hurling a tuck at him at the moment when Henri of Navarre was leaving the bed of this Jourgandine. We can understand how, under such amorous auspices as these, the Prince was shaken in his assault upon the virtue of a demoiselle of Rabours, who did not hesitate to prefer him that Admiral of Anville, 'who loved her more honestly.'" (History of prostitution: 412)

More adventurous amours.

"D'Aubigne merely cites in summary fashion 'the amours with Dayel, the Fosseuse; with Fleurette, daughter of a gardener of Nerac; with Martine, wife of a doctor in attendance on the Princess of Conde' with the wife of Sponde' with Esther Imbert, who died, along with the son which she had by the King, of poverty, as well as the father of Esther, who died of hunger at Saint-Denys, pursuing the fortunes of his daughter. Afterward came the affairs with Maroquin, an old Gascon debauchee, to whom this nickname had been given 'because she had a leatherish skin and some sort of syphilis' . . .; with an old baker woman of Saint-Jean; with Madame de Petonville' with la Baveresse (the Slobberer), 'so named because she sweated so;' with Mademoiselle Duras; with the daughter of a concierge' with Picotin, an oven keeper (pan-coussaire) at Pau; with the Countess of Saint-Megrin; with the nurse of Castel-Jaloux, 'who wished to give him a slash with a knife, because for a crown which he gave this lady he got back fifteen sols for the maquerelle;' and, finally, with the two sisters of l'Epee. . . ." (History of prostitution: 414)

|

| Henri d'Albret King of Navarre |

Henri IV's lovers were:

Bourbon Mistresses @YouTube

Madame Vincent.

She was one of the earliest of Henri IV's lovers.

Fleurette de Nerac (d.1592).

Lover in 1571-1572.

Daughter of: the gardener of the Chateau de Nerac

"In the long list of fifty-six mistresses of Henry IV, complied from contemporary records by M. de Lescure in the middle of the last century---a list which that historian rightly says is incomplete---the eighth name is that of Fleurette. This young girl is called by other writers Florette, and she is generally designated by them as being, not the eighth, but the first object of the adoration of Henri de Navarre. She was the daughter of the head gardener of the Chateau de Nerac, was sprightly, with laughing dark eyes, and not more than a couple of years older than the Prince. By this demoiselle of Bearn, of plebeian origin, the precocious Henri became a father for the first time. What became of her, subsequently, or of the child that she bore to the future King of Navarre, and later of France, the records do not say. Even had the Prince of Bearn, afterwards so ready to publicly acknowledge his illegitimate offspring, and to ennoble them, been his own master, he would scarcely have dared to have indulged his pride in early parentage, so far as to legitimise a child of such humble origin. Nor do we know what Queen Jeanne thought or said about the matter. She had, it is true, become by that time a rigid Calvinist, but she had been brought up in the giddy Court of her uncle, Francois I. Therefore, although we fortunately possess no proof of the damaging assertion, made by Henri III to the King of Navarre, that his mother's good name had not always been above suspicion, we may deem it probably that she was not too severe with her son for this first youthful fredaine [an escapade] , to be followed shortly by many more." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 24)

"In the long list of fifty-six mistresses of Henry IV, complied from contemporary records by M. de Lescure in the middle of the last century---a list which that historian rightly says is incomplete---the eighth name is that of Fleurette. This young girl is called by other writers Florette, and she is generally designated by them as being, not the eighth, but the first object of the adoration of Henri de Navarre. She was the daughter of the head gardener of the Chateau de Nerac, was sprightly, with laughing dark eyes, and not more than a couple of years older than the Prince. By this demoiselle of Bearn, of plebeian origin, the precocious Henri became a father for the first time. What became of her, subsequently, or of the child that she bore to the future King of Navarre, and later of France, the records do not say. Even had the Prince of Bearn, afterwards so ready to publicly acknowledge his illegitimate offspring, and to ennoble them, been his own master, he would scarcely have dared to have indulged his pride in early parentage, so far as to legitimise a child of such humble origin. Nor do we know what Queen Jeanne thought or said about the matter. She had, it is true, become by that time a rigid Calvinist, but she had been brought up in the giddy Court of her uncle, Francois I. Therefore, although we fortunately possess no proof of the damaging assertion, made by Henri III to the King of Navarre, that his mother's good name had not always been above suspicion, we may deem it probably that she was not too severe with her son for this first youthful fredaine [an escapade] , to be followed shortly by many more." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 24)

"Despite the surveillance of his stern Huguenot preceptor, Florent Chretien, Henri entered upon his career of gallantry at La Rochelle when he was barely fifteen. The object of this first attachment was a damsel named Florette or Fleurette, who would appear to have been a daughter of a gardener, and is said to have presented him with a son. . . . "(Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 2)

"After this singular debut [that is, affair with Madame de Beauvais], the monarch addressed the same homage to 'une petite jardiniere,' by whom he had a daughter, who was brought up without scandal and married secretly to a gentleman of some position. . . ." (Five Fair Sisters: 66)

Chateau de Nerac

"Henry III of Navarre, the future Henri IV, spent part of his youth in Nerac. A local legend suggests that he wooed Fleurette, daughter of (a) gardener, who drowned herself in the waters of the river in desperation because he left her. All that remains of this marble statue and plaque in the royal park." (Food and Travel)Suzanne des Moulins.

Lover in 1572?

Wife of: Pierre de Martines de Morantin (d.1591), Professor of Greek & Hebrew, University for Protestants.

Natural offspring: A son who died.

" . . . Among the balls and fetes which celebrated the conclusion of the peace at La Rochelle, Henri de Navarre, now a young and successful hero, was not long in discerning a very handsome face. It was that of a young married lady, wife of Pierre de Martines, an aged professor of Greek and Hebrew. Suzanne des Moulins, the spouse of the instructor in an University for Protestants largely endowed by the Bearnais, Coligny, and Prince Henri de Conde, was a compatriot of Henri de Navarre, who was not quite eighteen when he first met her. She was born at Arguedas, in Navarre, but, beyond the fact of her being many years the Professor's junior at the time when she was first distinguished by what the contemporary writers call the Prince's 'kindness,' the young lady's age is unknown. The warlike renown, the rank, and the good nature of one who was to become the King, soon won the heart and overcame the scruples of the fair Suzanne, and again, although Henri seems to have thrown no cloak over the liaison which soon took place between them, his strong-minded mother does not appear to have intervened to cause her son to behave with greater propriety." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 28)

". . . It was also at La Rochelle that, after a brief interval, we hear him laying successful siege to the heart of Suzanne des Moulins, wife of Pierre Mathieu, a professor at the University. This lady likewise presented him with a pledge of her affection, but the child also a son only lived a short time." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 2)

Madame de Martines's other lovers.

Madame de Martines's other lovers.

"According to La Confession de Sancy, that lively satire of the faithful follower and historian of Henri IV, Agrippa d'Aubigne, this tender-hearted lady found place in her affections for other lovers when the Prince had become as openly inconstant as he had been openly devoted. Among these was a man of considerable note as an author, the Seigneur de Fay, the grandson of de l'Hopital, the celebrated Chancellor of Catherine de Medicis." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 30)

Natural offspring.

Natural offspring.

"For five years after the death of her son by Henri de Navarre the amiable Madame de Martines had no children. Shen then gave birth in rapid succession to two sons and two daughters, but, like the son of a Royal father, these all died in early infancy. During her married life after, save for an occasional meeting, Henri had passed out of it, Susanne would not seem to have been inconsolable." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 30)

Effects of the affair on the lovers' families and society.

"The ministers of the Reformed religion at La Rochelle did not view the matter with equal complacency---they did not scruple to call the Prince to book from the pulpit on account of his misconduct. Bassompierre says in his Memoires: 'Being in the springtime of his youth at La Rochelle, Henry IV seduced a bourgeoise named the lady Martines, by whom he had a son, who died. The ministers and the consistory addressed public remonstrances to him in the Protestant meeting-house.' In spite of this public reprobation to which the Bearnais and his lightly conducted paramour were thus exposed, that the worthy Professor seems to have thought very little of the matter is evident from a further passage in the same Memoires: He did not even complain of the Prince's attentions, thinking that Madame Martinia and Henri did not go beyond the bounds of simple gallantry, and did not push the matter further than play'. . . [I]t is more than probable that, like many other husband whose wife has been honoured by the 'kindness' of Royalty, he found it more to his interest to pretend that he could not see that which the clergy declared to be an open scandal. He may even . . . have considered in the light of an honour the attentions to his young spouse of the Prince who had called him from Navarre to a lucrative position at Rochelle. Be that as it may, the Professor never treated Suzanne other than kindly, and when he died, twenty years later in 1591, expressed himself in most effusive terms in his will, and left her all his property." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 28)

Bretine de Duras.

Lover in 1573-1574.

Daughter of a miller

French aristocrat, beauty, courtier & royal mistress

1. Simon de Fizes, Baron de Sauve (d.1579) mar 1569

2. Francois de La Trémoille, Marquis de Noirmoutiers, mar 1584.

Natural offspring: Jeanne-Huguette de Beaune Semblançay (1572-?)

"Charlotte de Beaune-Sembancay (1551-1617) became Comtesse de Sauve on her marriage to Simon de Fizes (d.1579), Baron de Sauve. She took a second husband, Francois de La Tremoille, Marquis de Noirmoutier. Her numerous lovers included Henry of Navarre, d'Alencon, Souvre, and du Guast. Marguerite called her a 'Circe'. Henry of Navarre said that she was responsible for the bestiality which alienated him from d'Alencon. Of her many lovers, she remained most attached to Henry de Guise." (La Reine Margot: 481)

Bretine de Duras.

Lover in 1573-1574.

Daughter of a miller

|

| Charlotte de Sauve @Wikimedia |

Charlotte de Sauve (1551-1617)

Lover in 1573-1576.French aristocrat, beauty, courtier & royal mistress

1. Simon de Fizes, Baron de Sauve (d.1579) mar 1569

2. Francois de La Trémoille, Marquis de Noirmoutiers, mar 1584.

Natural offspring: Jeanne-Huguette de Beaune Semblançay (1572-?)

"Charlotte de Beaune-Sembancay (1551-1617) became Comtesse de Sauve on her marriage to Simon de Fizes (d.1579), Baron de Sauve. She took a second husband, Francois de La Tremoille, Marquis de Noirmoutier. Her numerous lovers included Henry of Navarre, d'Alencon, Souvre, and du Guast. Marguerite called her a 'Circe'. Henry of Navarre said that she was responsible for the bestiality which alienated him from d'Alencon. Of her many lovers, she remained most attached to Henry de Guise." (La Reine Margot: 481)

Charlotte became the mistress of Catherine’s son Francois, Duc d’Alencon and then of her son-in-law Henry of Navarre. Charlotte was also the mistress of Henri de Lorraine, Duc de Guise and was with him the night before his assassination at Blois (Dec 23, 1588). During the reign of Henry IV (1588–1617) Madame de Noirmoutiers attended the Bourbon court but though she was received there by the royal family, she never lived down her previous scandalous reputation. With the death of her husband (Feb, 1608), she became the Dowager Marquise de Noirmoutiers. Madame de Noirmoutiers died (Sept 30, 1617) aged sixty-six. Charlotte appears as a character in the historical novel entitled Evergreen Gallant (1965) by British novelist Jean Plaidy." (Women of History)

Louise de La Beraudiere

Louise de La Beraudiere (1530-1586)Lover in 1575.

Maid-of-honour to Catherine de' Medici, Maid of Honour to Marguerite de Valois

Daughter of: Louis de La Beraudiere.

Her other lovers were:

1. Antoine I de Navarre, Henri IV's father.

2. Henri III de France

Marguerite d'Avila (1553-1625)

Lover in 1575 & 1578-1579.

Cypriot lady.

Daughter of: Antoine d'Avila & Florence Synticlico.

Wife of: Jean d'Hemeries, Sieur de Villers, a Norman gentleman

Louise Borre (1555-1632).

Lover in 1575-1576.

Daughter of: Jehan Borre, a royal notary.

Wife of: Perrine Lebreton, mar 1603

Natural offspring:

1. Herve Borre (1576-1634)

Jeanne de Tignonville.

Lover in 1577-1578.

Baronne de Panges.

Daughter of: Lancelot de Montceau, Seigneur de Tignonville & President of Parliament of Paris

Wife of: Francois de Pardaillan, Baron de Panges.

"It was not, however, until the autumn of 1578 that Marguerite was permitted to join him, and, in the interval, his Majesty would appear to have got on excellently well without his consort. To this epoch belongs his affair with Mlle. de Tignonville, daughter of Lancelot de Montceau, Seigneur de Tignonville, first maitre d'hotel to the King of Navarre. So enamoured did he become of this damsel, that he made the long journey to Bearn, under the pretext of seeing his sister Catherine, in order to pay court to her. At first Mlle. de Tignonville would have none of him, but he is believed to have triumphed over her resistance, eventually, by the aid of a Gascon named Salboeuf, who, says, d'Aubigne, 'did not play the part of a gentleman in this matter.'" (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 3)

" . . . Nevertheless, the King of Navarre was at this very time engaged himself in casting sheep's-eyes, which for a time thrown in vain, at a very pretty and interesting young lady, one of his own subjects. We have mentioned how Henri had regained his sister Catherine from guardianship or imprisonment which she had been undergoing at the Court of France, and that she had then become a Protestant again, as she had been in her childhood. He now took her off to the Court of Navarre, which its King was in the habit of gathering around him alternately at the two Bearnese capitals, Nerac and Pau. There he appointed, as governess to his sister, now termed 'Madame,' a lady of noble birth, Madame de Tignonville. This lady had a young and beautiful daughter, Jeanne, for whom her amorous King was soon sighing full blast with all the fury of a furnace. The girl, however, was virtuous, or at any rate determined to remain chaste until her marriage. Thereupon Henri vainly imagined that he could employ his faithful follower and watch-dog d'Aubigne, to overcome the young lady's scruples. He had, however, got hold of the wrong man; there were not many things that d'Aubigne would not do in peace or war to oblige the King of Navarre, but to play the role of Mercury to his Jove was not one of them. Accordingly, in spite of prayers and menaces, and likewise various bad turns which the malicious Henri played his servant, the gallant d'Aubigne remained most obstinately incorruptible; and we honour him accordingly, as being a man of far more principle than his master." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre & Marguerite de Valois: 148)

'Thence the King of Navarre made his journey into Gascony. Thereupon the young King having commenced his amours with the young Tignonville, who, as long as she remained a maid, virtuously resisted, the King sought to employ Aubigne in the matter, having asserted, as a certain fact, that to him nothing was impossible." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre & Marguerite de Valois: 149)

"In the meanwhile Jeanne de Tignonville remained on her side equally inflexible, until the King of Navarre having provided her with a husband in the person of Francois, Baron de Pardaillan, comte de Pangeas, she considered that her reputation was no longer at stage, and yielded to her Sovereign's desires. At last, then, the Ling of Navarre was successful in attaining the object of his passion, apparently with no opposition on the part of Jeanne's husband, who, with the usual facility of the husbands of those days in the presence of royalty, doubtless eclipsed himself until the fickle fancy of the young King had been enchained elsewhere. . . ." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre & Marguerite de Valois: 150)

Dayelle the Cyprian (1553-1584)

Lover in 1578.

Spanish lady-in-waiting, Maid of Honour of Queen Marguerite.

Daughter of: Francisco de Ayala & Portia Pagano.

Wife of: Camille de Fera (1513-1594) mar 1580.

"The King had been previously 'very amorous' of one of these beautiful maids, so well trained, as Hardouin de Parefixe tells us, by the Queen mother 'to amuse the princes and the seigneurs and to discover all their thoughts.' This maid was La Dayelle, native of the Isle of Cyprus, who won her dowry by amusing Henri of Navarre, and who afterwards wed Jean d'Hemerits, a Norman gentleman. Dayelle had not occupied the King's attention seriously enough to distract him from his vagabond amours; he also had a 'kindly feeling' (bontes) in passing for the wife of the scholar, Martinius, professor of Greek and Hebrew, who insisted on believing that his Martine and the King 'would not carry things any further than a game,' as Colomiez says (in his Gaule Orientale, page 93).

After the departure of Dayelle, the King,' relates Marguerite, 'set about seeking for Rebours, daughter of the president of the Parliament of Paris, who was a malicious girl,' and one who had no love for the Queen but who did the latter all the bad offices of her power. This maid, who died a short time afterward at Chenonceaux, where Marguerite went to visit her and forgave her all, had given the King a rival in the hope of making a husband of this lover, who was Geoffrey de Buad, Seigneur de Frontenac. La Rebours was not yet dead when the King 'commenced to embark with Fosseuse, who was very beautiful and then quite a child and altogether innocent. Francoise de Montmorency, called La belle Fonsseuse, for the reason that her father was Baron of Fosseux, was one of the maids of honor of the Queen mother; but she consented to enter the house of Queen Marguerite, in order to be near the King, whom she love 'extremely,' although she had not 'permitted jim any privileges which decency might not permit;' but Henri was once more jealous of his brother-in-law, the Duke of Alencon, who was courting La Fosseuse at the same time; the latter, in order to remove his jealousy and let him know that she loved none but him, so abandoned herself to content him in all things that he might want of er that she unfortunately become pregnant.' Marguerite lent a hand in concealing this pregnancy, and it was she who took in the infant whom La Fosseuse brought into the world. This maid promised herself that she would one day supplant the Queen, and marry the father of her son. But the child did not live, and the mother, cast aside like all those who who preceded her, proceeded to wed, at the King's good pleasure, Francois de Broc, Seigneur de Saint_Mars." (History of prostitution: 417)

"In these pages we prefer to speak only of those love affairs of Henri's of which there is some evidence. Respecting his infatuation for Dayelle very few details have come down to us. We know, however, that he lost her when Catherine de' Medici, having established peace between him and her son Henri III, at least returned to Paris. For Dayelle went thither with the Queen-mother, and soon afterwards became the wife of a Norman noble, Jean d'Hemerits, Sieur de Villers. . . ." (The Favourites of Henry of Navarre: 55)

" . . . Henry's latest attractions were Victoria d'Ayala (dubbed Dayelle by Marguerite)... Considering her own behaviour Marguerite had little cause to complain about Dayelle and Fosseuse and indeed made light of the matter, describing Henry's penchant for young mistresses as an 'erreur de jeunesse'. . . ." (Honeyman. Shakespeare's Sonnets and the Court of Navarre: 57)

". . . Henri de Navarre paid more attention to the Cyprian beauty known as Dayelle. She and her brother, it appears, were of Greek birth, and had escaped from Cyprus, when in 1570 that island was wrested by the Turks from the Venetians. Coming to France. the brother was patronized by the Duke d'Alencon, who made him a gentleman of his chamber, while the sister was added to that battalion of frail fair ones with whom Catherine de' Medici loved to surround herself. Henri de Navarre had already met Dayelle in Paris at the time of his infatuation for Mme. de Sauves, but he had then paid little heed to her; whereas now it was Mme. de Sauves whom he neglected, reserving all his glances for the languorous eastern beauty of the almond-eyed Cyprian." (Vizetelly: 51)

". . . His independence had also allowed him to cultivate a penchant for sexual adventure. When his wife and mother-in-law joined him, Navarre [Henri IV] immediately became involved with Victoria de Ayata, a new Spanish lady-in-waiting to Catherine, Whatever its personal dynamic, religion and politics further complicated their relationship." (Wellman: 292)

Anne de Balzac de Montaigu.

Lover in 1578 or 1579.

Wife of

1. Francois de l'Isle &

2. Louis-Seguier de Brisson.

Marguerite de Rebours (1557-1610)

Lover in 1579.

Maid-of-honour to Queen of Navarre Marguerite de Valois 1579

Daughter of one Montabert, Sieur de Rebours, a Huguenot nobleman of Dauphine.

Mademoiselle de Rebours's other lovers were:

1. Charles de Montmorency, Duc de Damville.

2. Geoffroy de Buade, Seigneur de Frontenac.

"Madame de Sauve and the fascinating Mlle. Dayelle having followed Catherine to Paris, Henri turned for consolation to one of his wife's maids-of-honour, Mlle. de Rebours, 'a malicious girl,' says Marguerite, 'who disliked me and endeavoured by every means in her power to prejudice me in the eyes of the King my husband.' Mlle. de Rebours's favour, however, was not of long duration, for when the Court quitted Pau for Nerac, in the following June, she was ill and had to be left behind, and by the time she was sufficiently recovered to regain it, her place in the King's affections had been usurped by another of Marguerite's maids-of-honour, Mlle. de Fosseux. . . . " (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 6)

Mlle. de Rebours's physical appearance & personal qualities.

" . . . Marguerite, Mlle. de Rebours was a very malicious young person, who did not like her, but did every possible ill turn. Slight and slender, however, she was also very delicate, and thus Henri's intrigue with her was of short duration. 'Amidst these contrarieties,' writes Marguerite (referring to the dislike which the more zealous Huguenots evinced for her), 'God, to whom I always had recourse, at last took pity on my tears, and permitted that we should depart from that little Geneva, Pau, where, by a piece of good fortune for me, Rebours remained lying ill, in such wise that the King, my husband, losing sight of her, also lost his affection for her, and began to engage with Fosseuse, who was much prettier, and at that time young and very good-natured.'" (The favourites of Henry of Navarre: 57)

Mlle. de Rebours's personal & family background.

"There was a certain Mlle. de Rebours, whose parentage is somewhat doubtful, some authorities saying that she was the daughter of one Montabert, Sieur de Rebours, a Huguenot nobleman of Dauphine, killed at the St. Bartholomew massacre; while according to others her father was a judge, first at Calais, and later of the Parliament of Paris. L'Estoille chronicles a somewhat amusing jeu de mots respecting his personage, who was in the capital at the time Henri de Navarre besieged it. His troops having planted a couple of cannon on the height of Montmartre, were firing on the city when a ball from one of the guns broke one of M. de Rebours' legs. Thereupon, as he was suspected of secretly favouring the royal cause, the preachers of the League made a great joke of the affair, declaring from the pulpit that 'the cannon shots of the Royalists went a rebours.'" (The favourites of Henry of Navarre: 56)

Anne de Cambefort.

Lover in 1579.

"She threw herself out of the window when the King left her." (Histoire de France)

Arnaudine de Agen.

Lover in 1579.

Maid of Catherine Luc.

Catherine de Luc d'Agen.

Lover in 1579.

Daughter of a doctor in Agen

" . . . She gives birth to a child of the King. When the King abandons her, she lets herself die of hunger." (Histoire de France)

Aimee Le Grand.

Lover in 1579.

Francoise de Montmorency (1566-1641)

Lover in 1579-1581.

Maid-of-honour to Queen Marguerite 1579

Bridesmaid to Queen Catherine de' Medici.

Daughter of: Pierre I de Montmorency-Fosseux, Sire de Fosseuse & Marquis de Thury & Jacqueline d'Avaugour.

Wife of: Francois de Broc, Baron de Cinq-Mars, mar 1596.

"Henry IV was not called the green-gallant for nothing. In addition to his official mistresses, the king also lived small stories more or less short. The first of his known mistresses was Francoise de Montmorency-Fosseux, called the "beautiful Fosseuse". She was an unmarried girl, born in 1562 and who became the mistress of Henri IV in 1579, being one of the bridesmaids of Catherine de Medici. Francoise was the first love of the king who was suffering from his marriage with Marguerite de Valois. Francoise quickly became pregnant with Henri, which provoked the wrath of 'Queen Margot'. The latter arranged for the birth to take place as discreetly as possible. Francoise gave birth to a stillborn daughter in 1581 and was expelled by the wife of her lover in 1582. If Mlle de Montmorency had given birth to a son who had lived, it could have blocked access to the throne of Henri IV to the death of Henry III." (L'Envers de l'Histoire)

". . . (T)he king my husband, losing sight of her [Mademoiselle de Rebours], lost all his affection too, and began to flirt with Fosseuse, who was very pretty, quite a child, and very virtuous. . . .'" (The Marriages of the Bourbons, Vol 1: 188)

|

| Henry of Navarre & La Belle Fosseuse @Wikipedia |

"During their journey the King of Navarre fell ill, and Marguerite tells us how she nursed him for seventeen days and nights without undressing; and in this task she was aided by the Comte de Turenne, afterwards Duc de Bouillon. Her peace of mind, relative as it was, was soon disturbed once more. Troubles broke out in Guienne between the Catholics and the King of Navarre, and who should appear on the scene as a peacemaker, but the Duc d'Alencon, who soon managed to conclude a peace which was afterwards ratified by Henri III. The duke, unfortunately for all parties, fell in love with Fosseuse. Knowing that the King of Navarre would suspect her of furthering the suit of the duke, her brother, Marguerite relates how she implored him to take his departure, and Fosseuse, seeing his Majesty, whom she loved, exceedingly jealous, consented to become his mistress. What followed appears almost incredible. Fosseuse, when about to become a mother, gained complete ascendancy over the king, who not only neglected his wife, but wished to oblige her to accompany him and his mistress to Aigues Chaudes. Marguerite resisted, and in the end her husband and Fosseuse set out for the baths accompanied by Villesavin and Rebours. Marguerite shortly afterwards learned that the king had promised to marry Fosseuse if she were confined of a son. . . ." (The Marriages of the Bourbons, Vol 1: 189)

"The renewal of the civil war temporarily interrupted his Majesty's courtship of Fosseuse, and when, after some months, the conclusion of peace gave him leisure to resume it, he found, to his mortification, that he no longer had the field to himself. The Duc d'Anjou had been sent to Gascony to treat for peace on behalf of Henri III and after his diplomatic labours were over, he remained as a guest at his brother-in-law's court. Monsieur, who had a marvelous aptitude for making mischief wherever he went, did not fail to maintain his reputation in this respect. He fell in love with the fair Fosseuse, and, for a time, there reigned between him and his royal host a rivalry almost as bitter as had existed in the days when they were both at the feet of Madame de Sauve. . . ." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 3-4)

Xainte.

Lover in 1580.

Maid of honour to Queen Marguerite

"At the same time that he flirted with this ingenue, the Bearnais cast a favourable eye upon a soubrette in his wife's service called Xainte, 'avec laquelle il familiarisait.' The Queen, however, was not in a position to protest having a little affair of her own, with the handsome Vicomte de Turenne, afterwards Duc de Bouillon." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 7)

"Having seen Gabrielle d'Estrees,' continues Bassompierre, 'he became so enamoured of her that he forgot the Countess de la Roche-Guyon.

Madame de Sponde.

Lover in 1580.

Wife of: Jean de Sponde, a classical scholar

"Henri had upon his subsequent visits to La Rochelle various other tender love-passages with ladies of that Protestant city. Of his connection with Madame de Sponde, another Navarrese lady and wife of another classical scholar, who translated Homer and Hesiod, there is not much worthy of remark, save that d'Aubigne, who never loved the mistresses of the master whom he served so well, hated both the husband and wife, and abuses both alike." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 30)

Beneficiaries of the affair.

"Jean de Sponde evidently was one of those who profited by his wife's infidelities; he was appointed to a very high position at La Rochelle, which he filled very badly, and wherein he caused great municipal confusion by his mismanagement." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 30)

Anne de Petonville.

Lover in 1580.Marguerite de Gramont (1555-1620).

Lover in 1582.

Wife of: Philibert de Gramont (d.1580), Comte de Gramont and de Guiche, Governor of Bayonne, Seneschal of Bearn. mar 1567

A lover worthy of divorcing a wife?.

" . . . The passion of Henri IV for this lady was so great that he declared his intention of obtaining a divorce from Marguerite de Valois, for the purpose of making her his wife; a project from which he was dissuaded by D'Aubigny, who represented that the contempt which could not fail to be felt by the French for a monarch who had degraded himself by an alliance with his mistress, would inevitably deprive him of the throne in the event of the death of Henri III and the duc d'Alencon." (The Life of Marie de Medicis, Queen of France: 46)

A cut above the rest of royal lovers.

"Madame de Gramont, who was a year or two older than her royal lover, was a very different kind of woman from the frail beauties who had hitherto engaged Henri's attentions. In the first place, she was very wealthy, being the only child of Paul d'Andouins,Vicomte de Gramont, the favourite of Henri III, who was mortally wounded at the siege of La Fere in August 1580; and her affection for the king was quite disinterested. In the second, she was a woman of considerable intellectual attainments and most accomplished musician, and in 1673 had given proof of a courage and sang-froid very unusual in one of her sex, when she had saved the life of her father-in-law, attacked at the Chateau of Hagetmau, near Pau, by a band of Protestant rebels, led by the Baron d'Arras. Lastly, though she passed several years of her married life amidst the corrupting atmosphere of the dissolute Court of the Valois, where vice was the mode, and virtue, even ordinary decency, was mocked and derided, she has the great honour not to figure in the scandals to which the chroniclers of the time devote so many pages." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 14)

First encounter.

"It was not indeed, until after the death of her husband, when she was living at the Chateau of Hagetmau, that her liaison with the King of Navarre, whom she had known since the time when they were children, began. The date is uncertain, but it was probably shortly after the departure of Marguerite and the fair Fosseuse for Paris in January 1582, though some historians place it at the end of 1580. . . . " (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 15)

" . . . Henry of Navarre's eyes were at last opened, and he decided to escape from the Court of the Valois, and regain his liberty. He succeeded in his design and passing the Seine at Poissy, arrived first at Alencon and then at Tours. It was soon afterwards that Henry of Navarre went as a matter of duty to visit the Comte de Gramont, whose family had rendered him important services, and for the first time met Diane de Gramont, known as 'la belle Corisande.' The Comtes de Gramont were very devoted followers of the princes of Navarre . . . Philibert de Gramont, Comte de Guiche, fought by the side of Henry in his battles, lost his arm and soon afterwards his life in the service of his king. . . ." (Royal Lovers and Mistresses: the Romance of the Crowned and Uncrowned Kings and Queens of Europe: 25)

"It was during this period that the King of Navarre made the conquest of the Comtesse Diana de Guiche, the widow of Philibert de Gramont, who had fallen in the service of his Majesty. The countess, who went by the name of La belle Corisande, appears to have held a sort of court of love at her castle of Louvigny. The inflammable Henri de Navarre had no sooner seen this lady than he became violently enamoured of her, and aware of the scandalous life which his wife was leading in Auvergne, proposed to marry her. He is said even to have signed a promise to this effect with his blood, and to have consulted his advisers as to the expediency of divorcing Marguerite de Valois and marrying his new love. La belle Corisande had given Henri de Navarre very solid proofs of her affection for himself and his cause; she had pawned her broad lands and sold her jewels to enable him to pay his army. Henri at this moment, remarked Capefigue, despaired of ever becoming King of France, and seriously thought of founding a new kingdom composed of Aquitaine and Gascony. Now the house of Gramont-Guiche was descended in direct line from the Dukes of Gascony, and what could he do better than marry La belle Corisande, and share with her his new throne? . . . ." (The Marriages of the Bourbons, Vol 1: 198)

Why Diane d'Andouins?.

". . . Madame de Gramont inspired in the volatile heart of the Bearnais the love the most worthy, as well as the most durable, which he had yet experienced; he gave her his fullest confidence and treated her with almost as much respect as he would have shown to a queen." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 15)

"Henry was sufficiently enamoured of Corisande to make her a promise of marriage, signed in blood; to offer to recognize her son; and to weep bitterly when the one she gave him died in infancy. His love for her was augmented by the admiration and gratitude he felt towards the woman whose heroic devotion to him, during this war, went as far as to pledge lands and jewels in order to procure him men and horses. She was the soul of all his expeditions, a faithful friend in his days of need, and Henry, in his turn, gave her strongg proofs of his attachment, and it was no fault of his that these did not receive the seal of matrimony." (Royal Lovers and Mistresses: 26)

Promised marriage or true love?.

"Henry de Navarre dipped a pen in the blood of his wounds and signed a paper in which he gave his royal word to marry the beautiful Corisande, once he had rid himself, by means of a divorce, of his wife, Marguerite de Valois, the famous Reine Margot, to whom he was only nominally married. We are told that Corisande refused to listen to the King's protestations of love, or to lend a willing ear to his assiduities until the contract had been signed with his blood. To do justice, however to the Comtesse de Gramont, we must point out that she loved Henry for himself. Among the many mistresses of this king she was perhaps the only one who was disinterested. She loved him in the days of his adversity. He knew it, and he appreciated it. He was grateful for her affection, and out of gratitude he gave her that contract signed with his blood." (Royal Lovers and Mistresses: 27-28)

Affair's end & aftermath.

"We shall have to refer to two more letters to Corisande further on in connection with the King of Navarre's sister, Catherine de Bourbon. Suffice it to say that at this moment Corisande was terribly jealous, and continued to load the King of Navarre with reproaches in spite of all his protestations of fidelity. It was not until March, 1591, that the rupture came, and that Henri IV wrote his quondam mistress a letter which brought their liaison to a close. In a fit of jealousy she had presumed to revenge herself by meddling with the family affairs of his Majesty." (The Marriages of the Bourbons, Vol ume 1: 202)

"The fugitive attachments of the King of Navarre did not prevent him from continuing his correspondence with Corisande, whom he constantly assured of his unalterable fidelity; he wrote to her from the trenches of Arques, after the death of Henry III, and when he had become King of France, and this correspondence did not cease until 1591, or nearly two years after the monarch had fallen in love with La Be Gabrielle. It was brought to a close because Corisande, who had lost all her personal charms, and had become coarse and corpulent, vexed at the conduct of her lover, determined to revenge herself. For this purpose, contrary to the wishes of the king, she did what she could to favour the marriage of his Majesty's sister, Catherine de Bourbon, with the Comte de Soissons. She even persuaded them to get married secretly, in the absence of the king, who was campaigning in the company with Gabrielle d'Estrees. Henri IV, greatly irritated at this interference in his domestic policy, seized the opportunity to break off all further relations with Corisande. . . According to Sully, the Comtesse de Guiche was irritated not only because the king, having loved her, loved others, but because, when she had lost her attractions, he was ashamed of ever having loved her. . . ." (The Marriages of the Bourbons, Volume 1: 210)

Personal & family background.

Diane d'Andouins, Vicomtesse de Louvigni, dame de l'Escun, was the only daughter of Paul, Vicomte de Louvigni, Seigneur de l'Escun, and of Marguerite de Cauna. While yet a mere girl, she became the wife of Philibert de Grammont, Come de Guiche, Governor of Bayonne, and Seneschal of Bearn...." (The Life of Marie de Medicis: 46)

Diane's spouse & children.

" . . . On August 7, 1567, this same Philibert de Gramont and Toulongeon, Comte de Gramont, known as Comte de Guiche, Vicomte d'Aster, Mayor of Bordeaux, Governor of Bayonne, and Seneschal of Bearn, married Diane d'Andouins, Vicomtesse de Louvigny, the only daughter of Paul, Viscount de Louvigny, and Lord of Lescun. She was surnamed Corisande, after the fashion of the time which made the grand ladies of the Court of France adopt some name of a heroine, borrowed from the novels of the chivalrous middle ages. . . ." (Royal Lovers & Mistresses: 25)

Natural offspring: Gideon (1587-1588)

"Alas! Henri's fidelity to Corisande was very far from being so 'white and spotless' as he asserted. During the years of their liaison the names of quite a number of women are associated with his. His affair with the wife of the learned and unsuspecting Pierre Martine, of La Rochelle, belongs to this period, and about the same time his Majesty gained the favour of a certain Mlle. Esther de Boyslambert, of that town, who, in August 1587, presented him with a son. Henri lived quite openly with this lady in the Hotel d'Hure, Rue de Bazoges, at La Rochelle, to the great scandal of the Calvinist pastors, who exhorted him from the pulpit to amend the irregularities of his life. . . ." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 23).

Lover in 1582.

Vicomtesse de Duras.

Sister of Corisande

Wife of Jean de Durfort, Vicomte de Duras

Friend & Maid of Honour of Queen Marguerite de Valois

"Philibert de Gramont died in August 1580 at the siege of La Fere. Montaigne writes of accompanying the funeral cortege to Soissons in 'Of diversion.' In 1582 his widow became the mistress of the Protestant leader, Henry, the king of Navarre. She supported Montaigne's political career and became a conduit between him and Henry, including his two visits to the chateau de Montaigne in December 1584 and October 1587. Nearer the end of the book that would appear in 1580, Montaigne placed a long aside to Marguerite d'Aure-Gramont, Madame de Duras. Daughter of the governor of Bearn and sister of Philibert de Gramont, she married in 1572 Jean de Durfort, Viscount of Duras. He abjured his Protestant faith after the Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre and shifted his support to the Catholic forces, thereby earning the animosity of Henry of Navarre. . . ." (The Oxford Handbook of Montaigne: 589)

Diane d'Andouins (1554-1620)

Lover in 1582-1587.

Comtesse de Guiche, Vicomtesse de Louvigny, Dame de Lescun, Comtesse de Gramont y Guiche.

Daughter of: Paul Vicomte de Louvigny, Seigneur de l'Escun & Marguerite de Cauna.

Lover in 1582-1587.

Comtesse de Guiche, Vicomtesse de Louvigny, Dame de Lescun, Comtesse de Gramont y Guiche.

Daughter of: Paul Vicomte de Louvigny, Seigneur de l'Escun & Marguerite de Cauna.

Wife of: Philibert de Gramont (d.1580), Comte de Gramont and de Guiche, Governor of Bayonne, Seneschal of Bearn. mar 1567

A lover worthy of divorcing a wife?.

" . . . The passion of Henri IV for this lady was so great that he declared his intention of obtaining a divorce from Marguerite de Valois, for the purpose of making her his wife; a project from which he was dissuaded by D'Aubigny, who represented that the contempt which could not fail to be felt by the French for a monarch who had degraded himself by an alliance with his mistress, would inevitably deprive him of the throne in the event of the death of Henri III and the duc d'Alencon." (The Life of Marie de Medicis, Queen of France: 46)

A cut above the rest of royal lovers.

"Madame de Gramont, who was a year or two older than her royal lover, was a very different kind of woman from the frail beauties who had hitherto engaged Henri's attentions. In the first place, she was very wealthy, being the only child of Paul d'Andouins,Vicomte de Gramont, the favourite of Henri III, who was mortally wounded at the siege of La Fere in August 1580; and her affection for the king was quite disinterested. In the second, she was a woman of considerable intellectual attainments and most accomplished musician, and in 1673 had given proof of a courage and sang-froid very unusual in one of her sex, when she had saved the life of her father-in-law, attacked at the Chateau of Hagetmau, near Pau, by a band of Protestant rebels, led by the Baron d'Arras. Lastly, though she passed several years of her married life amidst the corrupting atmosphere of the dissolute Court of the Valois, where vice was the mode, and virtue, even ordinary decency, was mocked and derided, she has the great honour not to figure in the scandals to which the chroniclers of the time devote so many pages." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 14)

First encounter.

"It was not indeed, until after the death of her husband, when she was living at the Chateau of Hagetmau, that her liaison with the King of Navarre, whom she had known since the time when they were children, began. The date is uncertain, but it was probably shortly after the departure of Marguerite and the fair Fosseuse for Paris in January 1582, though some historians place it at the end of 1580. . . . " (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 15)

" . . . Henry of Navarre's eyes were at last opened, and he decided to escape from the Court of the Valois, and regain his liberty. He succeeded in his design and passing the Seine at Poissy, arrived first at Alencon and then at Tours. It was soon afterwards that Henry of Navarre went as a matter of duty to visit the Comte de Gramont, whose family had rendered him important services, and for the first time met Diane de Gramont, known as 'la belle Corisande.' The Comtes de Gramont were very devoted followers of the princes of Navarre . . . Philibert de Gramont, Comte de Guiche, fought by the side of Henry in his battles, lost his arm and soon afterwards his life in the service of his king. . . ." (Royal Lovers and Mistresses: the Romance of the Crowned and Uncrowned Kings and Queens of Europe: 25)

"It was during this period that the King of Navarre made the conquest of the Comtesse Diana de Guiche, the widow of Philibert de Gramont, who had fallen in the service of his Majesty. The countess, who went by the name of La belle Corisande, appears to have held a sort of court of love at her castle of Louvigny. The inflammable Henri de Navarre had no sooner seen this lady than he became violently enamoured of her, and aware of the scandalous life which his wife was leading in Auvergne, proposed to marry her. He is said even to have signed a promise to this effect with his blood, and to have consulted his advisers as to the expediency of divorcing Marguerite de Valois and marrying his new love. La belle Corisande had given Henri de Navarre very solid proofs of her affection for himself and his cause; she had pawned her broad lands and sold her jewels to enable him to pay his army. Henri at this moment, remarked Capefigue, despaired of ever becoming King of France, and seriously thought of founding a new kingdom composed of Aquitaine and Gascony. Now the house of Gramont-Guiche was descended in direct line from the Dukes of Gascony, and what could he do better than marry La belle Corisande, and share with her his new throne? . . . ." (The Marriages of the Bourbons, Vol 1: 198)

Why Diane d'Andouins?.

". . . Madame de Gramont inspired in the volatile heart of the Bearnais the love the most worthy, as well as the most durable, which he had yet experienced; he gave her his fullest confidence and treated her with almost as much respect as he would have shown to a queen." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 15)

"Henry was sufficiently enamoured of Corisande to make her a promise of marriage, signed in blood; to offer to recognize her son; and to weep bitterly when the one she gave him died in infancy. His love for her was augmented by the admiration and gratitude he felt towards the woman whose heroic devotion to him, during this war, went as far as to pledge lands and jewels in order to procure him men and horses. She was the soul of all his expeditions, a faithful friend in his days of need, and Henry, in his turn, gave her strongg proofs of his attachment, and it was no fault of his that these did not receive the seal of matrimony." (Royal Lovers and Mistresses: 26)

Promised marriage or true love?.

"Henry de Navarre dipped a pen in the blood of his wounds and signed a paper in which he gave his royal word to marry the beautiful Corisande, once he had rid himself, by means of a divorce, of his wife, Marguerite de Valois, the famous Reine Margot, to whom he was only nominally married. We are told that Corisande refused to listen to the King's protestations of love, or to lend a willing ear to his assiduities until the contract had been signed with his blood. To do justice, however to the Comtesse de Gramont, we must point out that she loved Henry for himself. Among the many mistresses of this king she was perhaps the only one who was disinterested. She loved him in the days of his adversity. He knew it, and he appreciated it. He was grateful for her affection, and out of gratitude he gave her that contract signed with his blood." (Royal Lovers and Mistresses: 27-28)

Affair's end & aftermath.

"We shall have to refer to two more letters to Corisande further on in connection with the King of Navarre's sister, Catherine de Bourbon. Suffice it to say that at this moment Corisande was terribly jealous, and continued to load the King of Navarre with reproaches in spite of all his protestations of fidelity. It was not until March, 1591, that the rupture came, and that Henri IV wrote his quondam mistress a letter which brought their liaison to a close. In a fit of jealousy she had presumed to revenge herself by meddling with the family affairs of his Majesty." (The Marriages of the Bourbons, Vol ume 1: 202)

"The fugitive attachments of the King of Navarre did not prevent him from continuing his correspondence with Corisande, whom he constantly assured of his unalterable fidelity; he wrote to her from the trenches of Arques, after the death of Henry III, and when he had become King of France, and this correspondence did not cease until 1591, or nearly two years after the monarch had fallen in love with La Be Gabrielle. It was brought to a close because Corisande, who had lost all her personal charms, and had become coarse and corpulent, vexed at the conduct of her lover, determined to revenge herself. For this purpose, contrary to the wishes of the king, she did what she could to favour the marriage of his Majesty's sister, Catherine de Bourbon, with the Comte de Soissons. She even persuaded them to get married secretly, in the absence of the king, who was campaigning in the company with Gabrielle d'Estrees. Henri IV, greatly irritated at this interference in his domestic policy, seized the opportunity to break off all further relations with Corisande. . . According to Sully, the Comtesse de Guiche was irritated not only because the king, having loved her, loved others, but because, when she had lost her attractions, he was ashamed of ever having loved her. . . ." (The Marriages of the Bourbons, Volume 1: 210)

Personal & family background.

Diane d'Andouins, Vicomtesse de Louvigni, dame de l'Escun, was the only daughter of Paul, Vicomte de Louvigni, Seigneur de l'Escun, and of Marguerite de Cauna. While yet a mere girl, she became the wife of Philibert de Grammont, Come de Guiche, Governor of Bayonne, and Seneschal of Bearn...." (The Life of Marie de Medicis: 46)

Diane's spouse & children.

" . . . On August 7, 1567, this same Philibert de Gramont and Toulongeon, Comte de Gramont, known as Comte de Guiche, Vicomte d'Aster, Mayor of Bordeaux, Governor of Bayonne, and Seneschal of Bearn, married Diane d'Andouins, Vicomtesse de Louvigny, the only daughter of Paul, Viscount de Louvigny, and Lord of Lescun. She was surnamed Corisande, after the fashion of the time which made the grand ladies of the Court of France adopt some name of a heroine, borrowed from the novels of the chivalrous middle ages. . . ." (Royal Lovers & Mistresses: 25)

Esther Imbert de la Rochelle (1565-1592/1570-1593)

Lover in 1587-1588.

Daughter of Jacques Imbert de Boisambert, Vogt (Bailiff) of Aunis & Master of Requests of the Royal Court & Catherine Rousseau

"Alas! Henri's fidelity to Corisande was very far from being so 'white and spotless' as he asserted. During the years of their liaison the names of quite a number of women are associated with his. His affair with the wife of the learned and unsuspecting Pierre Martine, of La Rochelle, belongs to this period, and about the same time his Majesty gained the favour of a certain Mlle. Esther de Boyslambert, of that town, who, in August 1587, presented him with a son. Henri lived quite openly with this lady in the Hotel d'Hure, Rue de Bazoges, at La Rochelle, to the great scandal of the Calvinist pastors, who exhorted him from the pulpit to amend the irregularities of his life. . . ." (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 23).

Benefits to the paramour.

Affair's end & aftermath.

"If we may believe L'Estoile, Henri treated this poor lady very shabbily. 'At the end of this year (1592),' he writes, 'a woman called Madame Esther, who had been one of the mistresses of the King at La Rochelle, pressed by necessity and seeing herself, owing to the death of her son, cast off and almost abandoned by his Majesty, came to seek him at Saint-Denis, to implore him to have pity upon her. But the King, hindered by other affairs, and having also his mind occupied by other amours, took no account of her and refused wither to see or to hear her. Upon which the poor creature, overwhelmed by sorrow and mortification, fell ill at the said Saint-Denis and died.'" (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 24). Reference: [Vizetelly, p. 292]

Maid-of-Honour to Queen Marguerite.

"That, instead of at once treating Esther with neglect, this young King endowed Esther with a pension is apparent from two documents still in existence, both headed 'De Par le Roy De Navarre,' signed 'Henry,' and counter-signed by 'Duplessis-Mornay, by the very express command of His Majesty.' These provide for the payment, quarterly in advance, of the sum of two thousand crowns, sols, valued at six thousand livres, tournois. They are dated at La Rochelle October 13th and 14th 1587. There is also still present in the archives of the Basses-Pyrenees the first receipt signed by Esther for her quarter's allowance, while four other receipts, given by her to the Treasurer-General of the King of Navarre, remain as further testimony to contradict the crude statement of d'Aubigne, followed by others, that Henri allowed the infant son of Esther Ymbert to die in poverty, of starvation." (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 35)

Esther Imbert's personal & family background.

"This young lady, called by some chroniclers merely Esther, by others Ester Imbert, or Ymbert, was the daughter of Jacques Ymbert, Seigneur de Boyslambert, a gentleman whom Michelet merely designates as 'an honourable Protestant Magistrate of La Rochelle.' He was, however, a man of property, and held various other appointments. His wife was Catherine Rousseau, and Esther, the eldest of their ten children, was baptized in the Protestant church of La Rochelle on January 5th, 1565. . . As the King of Navarre won this young lady to his will in 1586, Esther was twenty-one years of age when she became his mistress. As for her father having been 'an honourable magistrate,' it would appear rather as if he had trafficked in his daughter's shame with the King of Navarre. . . For we find Jacques Ymbert de Boyslambert about this time becoming Bailly of the Grand Fief of Aunis, and, a little later, receiving from the Prince who had seduced his daughter the high appointment of 'Counsellor and Master of Requests of the House of Navarre.' These facts do not seem to speak very highly of the father's honour and the presumption is that he deliberately sacrificed that of his innocent daughter to the whim of a debauched young Monarch, then thirty-three years of age." (: 30-31) " (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 34)

"This young lady, called by some chroniclers merely Esther, by others Ester Imbert, or Ymbert, was the daughter of Jacques Ymbert, Seigneur de Boyslambert, a gentleman whom Michelet merely designates as 'an honourable Protestant Magistrate of La Rochelle.' He was, however, a man of property, and held various other appointments. His wife was Catherine Rousseau, and Esther, the eldest of their ten children, was baptized in the Protestant church of La Rochelle on January 5th, 1565. . . As the King of Navarre won this young lady to his will in 1586, Esther was twenty-one years of age when she became his mistress. As for her father having been 'an honourable magistrate,' it would appear rather as if he had trafficked in his daughter's shame with the King of Navarre. . . For we find Jacques Ymbert de Boyslambert about this time becoming Bailly of the Grand Fief of Aunis, and, a little later, receiving from the Prince who had seduced his daughter the high appointment of 'Counsellor and Master of Requests of the House of Navarre.' These facts do not seem to speak very highly of the father's honour and the presumption is that he deliberately sacrificed that of his innocent daughter to the whim of a debauched young Monarch, then thirty-three years of age." (: 30-31) " (The Amours of Henri de Navarre and of Marguerite de Valois: 34)

Affair's end & aftermath.

"If we may believe L'Estoile, Henri treated this poor lady very shabbily. 'At the end of this year (1592),' he writes, 'a woman called Madame Esther, who had been one of the mistresses of the King at La Rochelle, pressed by necessity and seeing herself, owing to the death of her son, cast off and almost abandoned by his Majesty, came to seek him at Saint-Denis, to implore him to have pity upon her. But the King, hindered by other affairs, and having also his mind occupied by other amours, took no account of her and refused wither to see or to hear her. Upon which the poor creature, overwhelmed by sorrow and mortification, fell ill at the said Saint-Denis and died.'" (The Last Loves of Henri of Navarre: 24). Reference: [Vizetelly, p. 292]

Charlotte de Foulebon.

Lover in 1589.

Madame de Barbezieres-Chemerault.Lover in 1589.

Maid-of-Honour to Queen Marguerite.

Widow of: Francois de Barbezieres-Chemerault.

Henriette de Foulebon.

Duchesse de Beaufort

Duchesse de Verneuil

Marquise de Monceaux

Daughter of: Antoine d'Estrees, Baron de Boulonnois, Governor of the l'Ile de France & Francoise Babou de la Bourdaisiere.

Wife of: Nicole d'Amerval, Seigneur de Liancourt.

Gabrielle's physical appearance and personal qualities.

" . . . 'Madame Gabrielle was the most lovely woman without dispute in France: her hair was of a beautiful blonde cendree; her eyes blue and full of fire; her complexion was like alabaster; her nose well shaped and aquiline;a mouth filled with pearly teeth, and lips upon which the god of Love perpetually dwelt; a stately throat and perfect bust; a slender hand; in short, she possessed the deportment of a goddess---such were the charms which none could gaze upon with impunity." (History of the Reign of Henry IV: 150)

Prized physical attributes.

" . . . At seventeen, Gabrielle had the physical attributes prized in Henri's time---a fleshy body, a fair complexion, and full lips---although she lacked Corisande's quick wit and exalted tone. . . ." (Henri IV of France: His Reign and Age)

As described by a rival to king's amour.

"Gabrielle d'Estrees must have approximated pretty exactly to the feminine ideal of her age: long-limbed, blonde and pale of complexion. Her face 'was as smooth and translucent as a pearl, with all its delicacy and lustre'. This was not written by some flattering courtier but by a woman who had reason to be critical of Gabrielle: Mademoiselle de Guise, a rival for the king's favour. She continued: 'Though she wore a dress of white silk, it seemed black compared with the snow of her skin' x x x Gabrielle's diminutive blonde head seems relatively small on an over-long neck and a sturdily built body, and her finely waved hair, taken up in a severe coiffure, reinforces this impressions. . . ." (What Great Paintings Say, Vol 2: 204)

The beauty so long concealed in a feudal castle.

''Shortly after the accession of Henri Quatre to his precarious throne, he despatched on a mission to Monsieur D'Estrees the first gentleman of his chamber, the handsome and accomplished Duke de Bellegarde. This brilliant courtier gazed with wonder on the beauty so long concealed in the obscurity of a feudal castle. Her tresses glowed with burnished gold; her blue eyes sparkled with a dazzling fire, her complexion was 121 radiantly fair, her nose well shaped and aquiline, her mouth was well fitted with pearly teeth, and her lips resembled the all-compelling bow of the god of love. A stately throat, a gently swelling bust, a rounded arm and slender hand—these completed the charms which a fascinating address and natural elegance of movement rendered still more irresistible." (Women of History: 121)

Endowed from birth with all the gifts and graces of nature.