|

| The Three Nieces of Cardinal Mazarin Maria, Olympia & Hortensia Mancini |

The Mancini Sisters.

"Mazarin, now prime minister, remained for five years without any member of his family being near his person. But when he deemed his position to be sufficiently firmly established, he sent for, first, the eldest daughter of Madame Martinozzi, and two daughters and a son of the Mancinis. Madame de Noailles was deputed by his eminence to convoy his nieces from Rome, and Madame de Nogent awaited their arrival at Fontainebleau, whilst the Marquise de Senece was appointed their governess. The were at once received by the queen-regent with every mark of kindness, and all parties were anxious to see the children and pay their court to them. The all-powerful minister placed his nephew and nieces at once upon the same footing as princes and princesses of the blood. It was only five years afterwards that Mazarin sent for another batch of nieces. M. Renee insists upon this fact, which, he says, Sismondi, Roederer, Capefigue, and the Duke de Nivernais, a descendant of the Mancinis have all been in error upon. Laura Mancini and Anne-Marie Martinozzi were pretty girls, but Olympe was very dark . . . Anne-Marie was blonde with soft blue eyes. Laura was olive-complexioned, and pretty. Olympe had expressive eyes, a long face, and a sharp chin. The nephew was sent to the Jesuits' college, but the young ladies were all lodged with the cardinal at the Palais Royal, the queen's own residence. Mazarin had formerly resided at the Hotel de Cleves, but latterly he had taken up his abode with the queen, and herein lies the secret of the power of the wily Italian, of the reception given to his relatives, and of the scandal that found an outlet partly in Mazarinades, and ultimately in that rebellion known to history as La Fronde. . . When at length success attended upon his efforts, and he had once more established the queen at Paris, he sent for three more nieces, two Mancinis and one Martinozzi, besides a nephew, in order to extend his alliances. The eldest was Laura Martinozzi, who wedded the Connetable Colonna; and the third, Hortense, who became Duchess of Mazarin. The youngest, Marie-Anne, did not come from Rome till some time afterwards, and she became Duchess of Bouillon. . . Olympe Mancini was next wedded to a prince of the house of Savoy. Then Laura, Duchess of Mercoeur, died at nineteen years of age. . . The cardinal had also, as we have before seen, lost his eldest nephew; but he had two others, the eldest of whom became the Duke of Nevers; the youngest was killed, when only twelve years of age, by his fellow collegians, when tossing him in a blanket." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol 44: 407)

Also known as:

the Little Fish Women: "The other nieces, the court, the nation, and all Europe looked on at this duel between an all-powerful minister and a mere child, with differing feelings and impatient curiosity. The Mazarines were alarmed. These bold parvenus had not forgotten how the people of Paris, when they dismounted from their travelling carriages at the Louvre, had hailed them as the 'little fishwomen.' In their palaces, surrounded by a court more brilliant than that of the Louvre, they pictured to themselves how dreadful it would be when the fall of their uncle, like the tap of a wand in a fairy tale, should change their palaces to cabins, their rich robes into rags, and they trembled at the prospect. 'They beheld thenselves again in poverty,' writes the Abbe de Choisy. It was no comfort to them that the cardinal's conqueror was one of themselves. Among the Mazarines it was not safe to count too much on family affection." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 474)

The fates of the Mancini siblings.

"And in her own family what shipwrecks had taken place. Heaven's thunderbolts sent them back into obscurity. The Princesse de Conti, the saint of the family, was dead. The Duchess of Modena was dead, leaving a son weak in mind and body, and at the point of death. The beautiful Hortense was dead, the Duchess de Mazarin. Her husband went to England to claim her corpse, and carried it about with him ever after in his travels. Olympia, Countess de Soissons, was implicated in the great poisoning conspiracy in 1680. One night in January of that year she quitted a ball room, flung herself into her coach, and never stopped till she had crossed the frontier of France, which she never entered again. Marie Anne, Duchesse de Bouillon, who was implicated in the same affair, was exiled, recalled, and at length banished from the court for life. The brother alone survived, the Duke de Nevers, who wrote very pretty verses. But that was all he did or could do. If we look a little further into history we shall find that the blood of Mazarin, though it mingled with that of many illustrious houses, never seems to have brought with it good fortune. The house of D'Este, the Stuarts, the Vendomes, the Contis, the Bouillons, the Soissons, have all died out one after the other." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 482)

|

Laura Mancini

Duchesse of Mercoeur

|

1) Laura Mancini, Duchesse de Bourbon (1636-1657)

Wife of: Louis de Vendome, Duc de Vendome et de Mercoeur (1612-1669)

"We have seen that the eldest niece, Laura Mancini, was espoused at Bruhl, at the time of Mazarin's exile, by the Duke of Mercoeur. This young lady had been destined for the Duke of Candale, who died young, at Lyons. But it is doubtful if the marriage would ever have come off, for the duke was one of the handsomest and most gallant men of his day, and he kept postponing the wedding till his death. His friend Saint-Evremond said of him: 'In the latter years of his life all our ladies were in love with him. after having set them against one another by the interests of gallantry, he brought them all together in tears for his death.' The marriage of Laura with the Duke of Mercoeur was the source of much scandal. The duke was summoned before the parliament, and he excused himself in the best way he could, by saying that his marriage took place before the exile of the cardinal, and that he had only been to Bruhl to see his wife and not the exiled minister. The duke was ridiculed as a man without character; but this does not appear to have been substantiated by his conduct, for so great was his devotion to the cause of Mazarin, that he challenged his own brother, the Duke of Beaufort, in his defence; he put down the rebellion in Provence, and carried on a successful war in Savoy and Modena. . . ." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol 44: 410)

" . . . The nephew and nieces were expelled from France by parliament; they joined their uncle at Peronne, and together took refuge at Bruhl, near Cologne. One of the most curious results of this exile was the marriage of Laura. She had been affianced to the Duc de Mercoeur, brother to the 'Roi des Halles,' and the duke gallantly followed the exiles,a nd carried out his engagements, to the infinite annoyance and vexation of Conde. Mazarin, like the Medicis, always looked to the matrimonial alliances of his nieces as a means of attaining or securing power. He knew whence came his own successes, so he established an escadron volant to affirm and to consolidate them. He had already caught the Duke of Candale, the wealthy heir of the Epernon family, but the prize had been removed by death." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol 44: 409)

" . . . The nephew and nieces were expelled from France by parliament; they joined their uncle at Peronne, and together took refuge at Bruhl, near Cologne. One of the most curious results of this exile was the marriage of Laura. She had been affianced to the Duc de Mercoeur, brother to the 'Roi des Halles,' and the duke gallantly followed the exiles,a nd carried out his engagements, to the infinite annoyance and vexation of Conde. Mazarin, like the Medicis, always looked to the matrimonial alliances of his nieces as a means of attaining or securing power. He knew whence came his own successes, so he established an escadron volant to affirm and to consolidate them. He had already caught the Duke of Candale, the wealthy heir of the Epernon family, but the prize had been removed by death." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol 44: 409)

|

| Eugene-Maurice de Savoie-Carignan |

Wife of: Eugene Maurice, Comte de Soissons (1635-1673)

Mother of Eugene of Savoy.

"Olympe Mancini, who was brought up with the young prince afterwards Louis XIV, and was so familiar with him that even a closer intimacy was at one time dreamt of, was, after disputing their lovers with her fair cousins, wedded to Eugene de Carignan, of the house of Bourbon, in Savoy, and who was, in consequence, created Comte de Soissons. The marriage of Olympe did not, however, in any way interrupt the friendly relations that had so long existed between herself and the king. Louis XIV, who had been initiated into those arts in which he afterwards so much excelled by Cateau la Borgnesse, never passed a day without a visit to the Hotel de Soissons. The cardinal had to supply his nieces with hotels, at the same time that he conferred some provincial or army appointment on their husbands. Poor Olympe, who had been done out of the Prince de Conti, the Prince of Modena, and Armand de la Meilleraie, by her sisters and cousins, was also destined to be eclipsed in the king's favours by Marie Mancini,; but this did not last long, for after his marriage, Louis XIV, tired of the jealous Marie, renewed his intimacy with Olympe. The cardinal took advantage of the circumstance to get her appointed superintendent of the queen's household. As to the count, we are told that during the king's secession to Marie, he was much mortified at the neglect shown to his wife . . . The Count de Soissons was, however, so good a husband, that he was ever ready to fight for his wife's privileges. Thus a quarrel arose at court between the Duchess de Navailles, as dame d'honneur to the queen, and Olympe, as superintendent. . . ." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol 44: 413)

Her lovers were:

Her lovers were:

|

| Francois de Neufville 2nd Duke of Villeroy @Wikipedia |

French aristocrat & soldier.

Marshal of France 1693

Governor of the young Louis XV

Governor of Lyon

Son of: Nicolas V de Neufville, Marquis de Villeroy, Marshal of France, Governor of the young Louis XIV.

Husband of: Marguerite-Marie de Cosse-Brissac (1648-1708) mar 1662

"Villeroy was a childhood friend of King Louis XIV and was protected and advanced by him through his career. Villeroy was the governor of Louis XV during the child king's regency before falling into disgrace for plotting against Philippe II of Orleans in favour of Philip V of Spain. . . ." (The Art of Fencing Reduced to a Methodical Summary: 1)

"Their exile was not, however, of long duration, and, at the end of a few months, Olympe returned to Paris and resumed her functions as Superintendent of the Queen's Household and her life of pleasure and intrigue. The King, however, seldom visited the Hotel de Soissons, and treated the countess somewhat coldly, if always with courtesy. To console herself for the loss of Vardes, Olympe took a disciple of his, the Marquis de Villeroi, called by the ladies 'le Charmant' into favour, and admitted him to her hotel on the same footing as that which that Titan of intrigue and gallantry had formerly occupied. If we are to believe the chansons of this time, M. de Villeroi had more than one coadjutor in his office of amant-en-titre; but that does not seem to be the opinion of the best-informed contemporary writers, and historians like Wackenaer, who accuse the countess of leading a life depravity, probably do her an injustice. She was far too haughty and fastidious ever to stoop to vulgar amours. Let us, however, leave Olympe for a time to speak of the fortunes of her sisters." (Fair Five Sisters: 252)

|

| Louis XIV de France by Charles Le Brun, 1661 @ Palais de Versailles |

2) Louis XIV de France (1638-1715)

Lover in 1654-1657, 1660-1661.

|

| Marie Mancini |

" . . . Mary de Mancini was one of the most remarkable women who ever graced a court. With a face attractive to all without being beautiful; a person which, even then, gave its early promise of what its maturity was to be; an eye of such liquid lustre that it revealed beyond words the emotions of the heart, a bearing which was the result of a nature guided by grace and a voice capable of such clear and soft expression that it enchanted all listeners; Mary de Mancini possessed in addition a genius, great, substantial and extensive, subjected to thorough discipline, and capable of the grandest conceptions. . . ." (The American Review, Vol. 2: 488)

Her true color.

"Every one knows how great nature's skill in hiding the defects of a face under the spell of youthful brilliancy; but its skill in hiding the distortions of the soul under the ardor and grace of youth has been less ofted remakred upon. At twenty a woman is almost always lovable. Moral ugliness develops only with years, and the world wonders why a woman has so altered. Her disposition may not have altered, it may ony have begun to exhibit itself. People belonging to the French court who knew Marie Mancini in the days of her love passages with Louis XIV, had never suspected in her the instincts of a vulgar adventuress. Her youth had deceived them. They gave her credit only for gaiety, and a great power of enjoyment. In less than ten years the brilliant favorite showed herself in her true colors. What we have to tell more of her will read like the adventures of some circus queen." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 479)

Marie at 40.

"As everything with Marie Mancini was doomed to be strange, she grew beautiful when she was about forty. The ugly little gipsy (sic), with her long, thin arms, was not longer either thin or dark-skinned. Her figure was fine, her bright eyes had grown soft and touching, her hair and teeth remained perfect. Her very lack of repose had its charm. . . ." (Princesses & Court Ladies: 68)

Transformation of Marie Mancini at 40 years old.

"That everything concerning Madame Colonna might be extraordinary, and out of the usual course of things, she became beautiful when was nearly forty. The ugly little brown girl, with arms like thread-papers, was no longer lean nor dark. Her figure was beautiful, her complexion clear and fair, her keen eyes had acquired a pathetic look, her hair and teeth had always been superb, and still remained so. She had a little air of nervous agitation which became her. . . ." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 482)

Wife of: Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna, Duca di Palliano (1637-1689)

8th Duca and Principe di Paliano; Hereditary Grand Constable of Naples and

Knight of the Golden Fleece.

Her lovers were:

1) Baron de Banier (d.1683)

Swedish aristocrat

Son of: General Banier, Swedish aristocrat & general

" . . . In 1683 when not far off her fortieth year, the Baron Banier, a handsome, romantic young boy and son of one of Gustavus Adolphus's generals, came to London, and fell in love with Madame de Mazarin. It mattered not to him that she laughed at him, he went about the town with her name on his lips heedless of ridicule. Suddenly this harmless flirtation became tragic. Her nephew, the young Chevalier de Soissons fell head over ears in love with her. Maddened by his horrible passion, he must needs take it into his head to be jealous of his Swedish rival. The two young fellows, blind to all sense of decency, to the eclat of such a duel, met, and the Chevalier de Soissons left Banier dead upon the field of dishonour. The noise of such a scandal may be imagined. The Chevalier would not, or could not, flee; he was arrested and tried, and without doubt, but for the pulling of many strings behind the scenes, would have been executed. 'It is fire not blood that flows in the veins of us Mancinis,' he is reported to have said. Thanks to the laxity of the laws in his time, the flaming young Chevalier was suffered to go to Malta and join the Order of the Knights Templars, among whom, far from his beautiful aunt, the fates granted him a few years of obscurity in which to cool." (Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: Histoirettes of the Restoration)

" . . . In 1684, her nephew, the Chevalier de Soissons, visited England, and conceived for his aunt, who, though now approaching her fortieth year and already a grandmother, was still almost as beautiful as ever, a most violent passion. The latter, however, repulsed him with horror, her heart at that moment being fully occupied by a fascinating Swedish nobleman, the Baron the Banier, son of the general of that name who had distinguished himself under Gustavus Adolphus. Mad with jealousy, the chevalier challenged the baron to a duel, and wounded him so severely that he died a few days later. 'I have told my son,' wrote Madame de Sevigne, 'about this combat of the Chevalier de Soissons. We could not have believed that the eyes of a grandmother could work such havoc.' This affair caused a terrible scandal, and M. de Soissons had to stand his trial for manslaughter. Madame de Mazarin was in despair; she denied herself to nearly all her friends, draped her rooms in black, and spoke of withdrawing to a convent in Spain. But this desire for a conventual life did not last long, and was replaced by a violent passion for play, and in particular for the fascinating game of bassette, which absorbed her to the exclusion of all other interests." (Rival Sultanas: Nell Gwyn, Louise de Keroualle, and Hortense Mancini: 355)

"It was also at this epoch of her life that occurred the strange incident of her own nephew, one of the sons of Olympe, the Chevalier of Soissons, who had come over to England, falling in love with her, and challenging her then favourite, the Baron de Banier, whom he was unfortunate enough to kill in a duel. . . Hortense was much afflicted for a time by the loss of her lover; so much so, that she closed her house, put herself in mourning, and even meditated withdrawing to a convent." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol. 44: 421)

" . . . In 1684, her nephew, the Chevalier de Soissons, visited England, and conceived for his aunt, who, though now approaching her fortieth year and already a grandmother, was still almost as beautiful as ever, a most violent passion. The latter, however, repulsed him with horror, her heart at that moment being fully occupied by a fascinating Swedish nobleman, the Baron the Banier, son of the general of that name who had distinguished himself under Gustavus Adolphus. Mad with jealousy, the chevalier challenged the baron to a duel, and wounded him so severely that he died a few days later. 'I have told my son,' wrote Madame de Sevigne, 'about this combat of the Chevalier de Soissons. We could not have believed that the eyes of a grandmother could work such havoc.' This affair caused a terrible scandal, and M. de Soissons had to stand his trial for manslaughter. Madame de Mazarin was in despair; she denied herself to nearly all her friends, draped her rooms in black, and spoke of withdrawing to a convent in Spain. But this desire for a conventual life did not last long, and was replaced by a violent passion for play, and in particular for the fascinating game of bassette, which absorbed her to the exclusion of all other interests." (Rival Sultanas: Nell Gwyn, Louise de Keroualle, and Hortense Mancini: 355)

"It was also at this epoch of her life that occurred the strange incident of her own nephew, one of the sons of Olympe, the Chevalier of Soissons, who had come over to England, falling in love with her, and challenging her then favourite, the Baron de Banier, whom he was unfortunate enough to kill in a duel. . . Hortense was much afflicted for a time by the loss of her lover; so much so, that she closed her house, put herself in mourning, and even meditated withdrawing to a convent." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol. 44: 421)

|

| Charles V of Lorraine @Wikipedia |

2) Charles V de Lorraine (1643-1690)

Duc de Lorraine & Bar 1675

Husband of Eleonore von Osterreich. mar 1678

"Monsieur de Lorraine, who loved her passionately, had been pressing her to marry him for a long time and continued in that pursuit even after the death of Monsieur le Cardinal. The Queen Mother, who did not want her to stay in France under any circumstances, ordered Madame de Venelle to break up that courtship whatever the cost, but all their efforts would have been useless if reasons unknown to everyone had not coincided with them. And although the king had the generosity to let her choose whomever she wanted to marry in France if Monsieur de Lorraine did not please her, and although he showed deep displeasure at her departure, her unlucky star led her to Ital,y against any number of good reasons. . . ." (Memoirs: 37)

" . . . No sooner had the cardinal given her permission to come back to Paris than she set up a romantic love affair, even more ardent than that with King Louis, with Prince Charles of Lorraine. An Italian abbe carried messages between them. They met continually by appointment in churches and in walks or rides. The affair had a somewhat disreputable air of intrigue, but Marie was no longer disposed to keep within the bounds of conventionality. She was desperately in love with Prince Charles. She insisted on becoming a princess of Lorraine. She vowed a hundred times 'that she would marry him or go into a nunnery.' She had not said so much for Louis XIV, a fact which Louis remembered subsequently. Prince Charles was completely captivated; Like the king his head had been turned by contact with this daughter of the southern lands." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 476)

" . . . When the French prince Charles de Lorraine showed interest in her, she did not hesitate to encourage him. And when her uncle rejected Lorraine's proposal, she understood that she had no alternative but to accept Colonna. La Verite makes it quite clear that she did so for pragmatic reasons. She foresaw that her position would become increasingly precarious, and even though the king grew more friendly after Mazarin's death, she had no illusions about her long-term prospects. . . ." (Women and the Politics of Self-representation in Seventeenth-century France: 115)

|

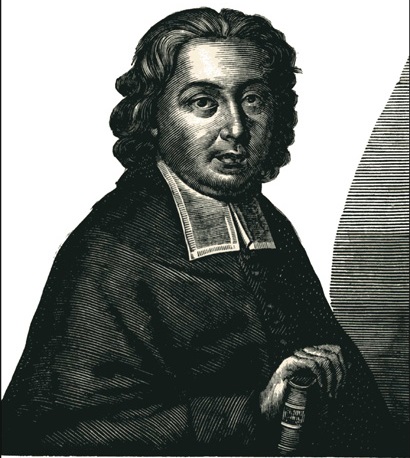

| Cardinal Chigi 17th c. |

Cardinal-priest 1657; Governor of Fermo, Tivoli; Ambassador to Avignon; Arch-priest of Basilica of Laterano; Librarian of the Vatican; Marchese di San Quirico 1677

Son of: Mario Chigi & Berenice della Ciaia, Nephew of Pope Alexander VII.

"First of all came a cardinal, Flavio Chigi, who was ugly to look at, with an olive complexion, a round face, and big eyes which seemed ready to pop out of his head, but he was the nephew of a pope, dissipated and jovial. There was no kind of folly that la Connetable did not make him commit. Once when he was expected to preside over a congregation in a meeting of one of the religious orders, she carried him off in her carriage, 'not more than half dressed,' tool him out of the city, and kept him until nightfall. Another time she surprused him still in bed, took possession of his clothes, dressed herself as a cardinal, and wanted to give audience in his place to those waiting in his ante-chamber. Another time they went together on a hunting party which lasted a fortnight, during which they camped out in the woods." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 478)

"First came a cardinal, Flavio Chigi, ill-favoured, dark-skinned, with a round face and pop-eyes that always seemed ready to fall out of their sockets; but he was nephew to a pope, gay and dissolute. Madame Colonna caused him to play all sorts of antics. One day when he was expected to preside over some church assembly she carried him off in her coach 'only half dressed,' took him into the country and kept him till evening. Another time she found him in bed, ran away with his clothes, dressed herself as a cardinal, and vowed she would receive in his stead. Once, they spent a fortnight hunting and camping in the woods." (Princesses & Court Ladies: 56)

A very worldly man, an amorous cardinal.

"Tradition describes Flavio Chigi as a very worldly man, involved in many love affairs. John Forsyth, during his visit in 1802 to Italy, wrote that Cetinale 'owes in celebrity to the remorse of an amorous cardinal who, to appease the ghost of a murdered rival, transformed a gloomy plantation of cypress into penitential Thebaid, and acted there all the austerities of an Egyptian hermit.' The sinful life of Flavio Chigi might have been exaggerated to the point of attributing to him even murder, but no historical evidence sustains the claim. Francis Haskell quotes a report by Ferdinando Raggi, a Genoese diplomatic agent in Rome, stating that Flavio 'only thought of hunting, of conversations and of banquets in order to overcome the venereal impulses which powerfully raged [in] him.' Flavio collected unusual paintings for a prelate, such as the sensual 'Female Bath by Michelangelo. . . ." (Sacred Gardens and Landscapes: Ritual and Agency: 242)

" . . . Flavio received an enormous income from his uncle, which allowed him to purchase many estates and undertake his own building initiatives, such as the palace of Formello, the villa of Versaglia, the beautiful palace of Piazza SS. Apostoli, restored by Gianlorenzo Bernini, and Cetinale. His private collections included paintings by Veronese, Titian, Palma, Caracci, Guercino, Guido Reni, Poussin, Salvator Rosa, Pietro da Cortona, Baciccio,, Carlo Maratta, and Mola. He owned a collection of classic statues and a Wunderkammer in his Casino alle Quattro Fontane.

" . . . Flavio received an enormous income from his uncle, which allowed him to purchase many estates and undertake his own building initiatives, such as the palace of Formello, the villa of Versaglia, the beautiful palace of Piazza SS. Apostoli, restored by Gianlorenzo Bernini, and Cetinale. His private collections included paintings by Veronese, Titian, Palma, Caracci, Guercino, Guido Reni, Poussin, Salvator Rosa, Pietro da Cortona, Baciccio,, Carlo Maratta, and Mola. He owned a collection of classic statues and a Wunderkammer in his Casino alle Quattro Fontane.

|

| Louis XIV of France 1664 |

Lover in 1658-1660.

" . . . Marie did not consummate her relationship with the Sun King. His love for her was a somewhat idealistic one, but he was so besotted that he wanted to marry. Eventually, Cardinal Mazarin and Anne of Austria separated the couple, banishing Marie into exile and arranging Louis' marriage to his cousin, Maria Theresa of Spain. In 1661, Marie was married off to an Italian prince, Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna, who remarked after their wedding night that he was surprised to find her a virgin as one does not normally expect to find 'innocence among the loves of kings'. (from Antonia Fraser's book Love and Louis XIV)." (Celebs Bio)

" . . . Marie did not consummate her relationship with the Sun King. His love for her was a somewhat idealistic one, but he was so besotted that he wanted to marry. Eventually, Cardinal Mazarin and Anne of Austria separated the couple, banishing Marie into exile and arranging Louis' marriage to his cousin, Maria Theresa of Spain. In 1661, Marie was married off to an Italian prince, Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna, who remarked after their wedding night that he was surprised to find her a virgin as one does not normally expect to find 'innocence among the loves of kings'. (from Antonia Fraser's book Love and Louis XIV)." (Celebs Bio)

First encounter.

" . . . Then, as Marie attended her dying mother in late 1656, she was 'discovered' by the young king, who made daily visits to her mother's bedside. He was struck by her lively wit; love blossomed and so did Marie herself; and for two years she lived a life of idyllic romance. . . ." (Nelson & Mancini: 3)

|

| Philippe de Lorraine-Armagnac @Wikipedia |

4) Philippe de Lorraine-Armagnac (1643-1702)

Chevalier de Lorraine

Her nephew.

"It will thus be seen that the duchess had begun to form a decided taste for intellectual pleasures; but this did not prevent her from indulging in numerous gallantries, one of which had a most tragic termination. Some years after her arrival in England, she was visited by her nephew, the Chevalier de Soissons, Olympe's youngest son. The chevalier 'breathed the contagious air of the house, and conceived for his aunt, who, though approaching her fortieth year and already a grandmother, was still almost as beautiful as ever, a most violent passion. Hortense, however, repulsed him with horror, her heart not being fully occupied by a fascinating Swedish nobleman, the Baron de Banier, son of the general of that name who had distinguished himself under Gustavus Adolphus. Transported with jealousy, the Chevalier challenged the baron to a duel, and wounded him so severely that he died a few days later. This affair caused a terrible scandal, and M. de Soissons was arrested and had to stand his trial for manslaughter. . . ." (Five Fair Sisters: 397)

"Then came the infamous Chevalier de Lorraine, exiled in spite of the tears of monsieur, brother to Louis XIV. Even in Rome, where Cardinal Chigi could, without exciting any indignation, preside over the congregations, the chevalier was black- balled. It was whispered that Madame la connetable, in monsieur's name, had given him 'a hunting suit worth a thousand pistoles, covered with a quantity of ribbons, the most beautiful and expensive that could be found in Paris.' The 'little fish-monger' of Rome could not resist the temptation of showing herself in her native town in company with so gorgeous a cavalier; the Chevalier de Lorraine was always at her side. The connetable became very angry. Fate had played him the trick of giving him a jealous nature and marrying him to a Mazarin. . . ." (Barine: 57)

"Then came the infamous Chevalier de Lorraine, banished from France in spite of the discreditable tears of Monsieur, Louis XIV's brother. Even in Rome, where Cardinal Chigi would, without shocking public opinion, preside over public meetings of religious orders, society refused to admit the chevalier. He insinuated himself into the circle around Madame Colonna by offering her, in the name of the Monsieur, 'a hunting outfit valued at a thousand pistoles, adorned with an infinite number of the most beautiful and costly ribbons that could be bought in Paris.' She, who was once called the little fish girl of Rome, could not resist the pleasure of exhibiting herself in her native city adorned with so many ribbons, the gift of a prince, and after that the Chevalier de Lorraine found himself established at her house on terms of intimacy and consideration. The Constable was very angry. Heaven, when it gave him a Mazarine for a wife, should have abstained from giving him a jealous disposition. He had shut his eyes when the cardinal was in the ascendant, but the chevalier was too much for him. 'However,' says his wife in her 'Apology,' 'I answered him roundly.' The Constable then sent a monk to remonstrate with her as a sinner. She took the monk by the shoulders and turned him out of doors. Cardinal Chigi, jealous on his own account, next ventured to exhorther. Whereupon they quarrelled irreconcilably. Rome gossiped, but the angry husband was powerless; all he could do was to find fault, and to fee spies." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 478)

" . . . The relations of La Connetable, as Marie was called, with the chevalier became at length so notorious, that, with the perspective of an imprisonment at Palliano, a stronghold of the connetable's on the frontiers of the Roman States, she fled with Hortense to Civita Vecchia, whence they made their escape in a felucca to Provence. The two sisters were, however, arrested at Aix, disguised in the habiliments of the male sex. Hortense was allowed to proceed into savoy, whilst Marie found a temporary shelter in the Abbaye du Lys. . . ." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol 44: 418)

"A quotation from the pen of Madame la Connetable will best show into what depths she next descended. She says: 'In spite of all that had passed the chevalier came every day to see me, and when the weather permitted we always walked together. We chose for our walks the shores of the Tiber near the Porto del Popolo, where I had had a little house built for me to bathe in . . . It was not for love, as my enemies have asserted, but our of pure gallantry that the chevalier, seeing me in the water up to my throat, implored mee to permit him to have my picture taken in that position, saying that so perfect a form, with so perfect a form, with so lovely a face might have inspired a Stoic with passion.' But the Constable was so jealous as to think that things in that bathing house were not conducted with strict propriety. Such an idea was most scandalous, and most unjust, for his wife tells us: 'My people can testify that I never went from under cover of the bathing house until I had on a gauze bathing dress which I had had made on purpose, and which came down to my heels.' But the Constable, not satisfied, gave so my proofs of jealousy unbecoming in a man of his position, that at last his wife resolved to elope from a husband who could be unreasonable." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 479)

|

Hortense Mancini 1671 |

Hortense's physical appearance and personal qualities.

"Hortense was quite the catch. Her black hair tumbled to her waist; her sparkling eyes changed color with the light. She was tall and slender, an accomplished sportswoman, musician, and linguist. And of course her pedigree was impeccable. In short, other than being French, she would have made the perfect queen." (History Hosdens, 2007)

". . . As if she had taken the idea to visit her former suitors in turn, she decided upon going to England, which she reached in the month of December, 1675, and where she was destined to remain till her death in 1699, twenty-four years later. . .

"She was now thirty. . . Her appearance on her arrival in London may be imagined by the following description by Forneron: 'The Duchesse de Mazarin was one of those Roman beauties in whom there is no doll-prettiness, and in whom unaided nature triumphs over all the arts of the coquette. Painters cold not say what was the colour of her eyes. they were neither blue nor grey, not yet black nor brown nor hazel. Nor were they languishing nor passionate, as if either demanding to be loved or expressing love. They simply looked as if she had basked in love's sunshine. If her mouth were not large, it was not a small one, and was suitably the fit organ for intelligent speech and amiable words. All her morions were charming in their easy grace and dignity. Her complexion was softly toned and yet warm and fresh. It was so harmonious that though dark she seemed of beautiful fairness. Her jet-black hair rose in strong waves above her forehead, as if proud to clothe and adorn her splendid head. She did not use scent.' . . . ." (The Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: 40)

|

| @V&A |

Wife of: Armand-Charles de La Porte, Duc de La Meilleraye (1632-1713)

"All this time a youth of low parentage, Armand de la Porte, son of a soldier of fortune, Marshal de la Meilleraye, loved Hortense for her own sake, and that to such a degree that he used to say he would wed her even if he was to die three months afterwards. Mazarin, returning from the conferences at the Pyrenees, stricken by death, selected this true lover for his heir, on the condition that he would assume his name and arms. Thus for the trouble of wedding the person he loved, one of the prettiest women in France too, this fortunate youth became Duke of Mazarin, one of the wealthiest men in the kingdom, and governor of Alsace, Brittany, and Vincennes. The cardinal, dying shortly afterwards, the young couple went to reside at the Palais Mazarin, which is said to have surpassed the Louvre in magnificence." (Bentley's Miscellany, Vol. 44: 419)

Hortense's spouse & children.

She married Armand-Charles de la Porte, Duc de La Meilleraye (1632-1713) mar 1661 .

"On 1st of March 1661, at the age of fifteen she was married to one of the richest men in all of Europe, the Duc de Mailleraye. Her new husband, Armand-Charles was twenty-nine years old and probably due to his enormous fortune had been allowed to have his own way for a very long way (time?). It meant that he fell into some very peculiar modes of behaviour. It is said that he coupled extreme sexual jealousy towards his young wife with an over the top sense of morality. To Hortense he was insanely jealous and distrustful." (The Stuart Kings)

" . . . Both the king of England and the duke of Savoy courted her, but as it turned out Mazarin had to settle for a less illustrious match, bestowing Hortense on Richelieu's nephew, Armand de la Meilleraye, who had fallen desperately in love with her and vowed to marry no one else. Mazarin made it a condition of the agreement that Meilleraye would henceforth be called the duc de Mazarin. In return he bequeathed him the major part of his fortune and his priceless art collections." (Women and the Politics of Self-representation in Seventeenth-century France: 85)

"On 1st of March 1661, at the age of fifteen she was married to one of the richest men in all of Europe, the Duc de Mailleraye. Her new husband, Armand-Charles was twenty-nine years old and probably due to his enormous fortune had been allowed to have his own way for a very long way (time?). It meant that he fell into some very peculiar modes of behaviour. It is said that he coupled extreme sexual jealousy towards his young wife with an over the top sense of morality. To Hortense he was insanely jealous and distrustful." (The Stuart Kings)

" . . . Both the king of England and the duke of Savoy courted her, but as it turned out Mazarin had to settle for a less illustrious match, bestowing Hortense on Richelieu's nephew, Armand de la Meilleraye, who had fallen desperately in love with her and vowed to marry no one else. Mazarin made it a condition of the agreement that Meilleraye would henceforth be called the duc de Mazarin. In return he bequeathed him the major part of his fortune and his priceless art collections." (Women and the Politics of Self-representation in Seventeenth-century France: 85)

"Her sister Hortense had already done the same thing. It is true that the Duke de Mazarin was a kind of madman, with whom no woman could have lived in peace. The duchess had come to Rome, and as she had had experience in elopements, and had crossed France in the disguise of a man, her sister Marie begged her to go back with her to France. They left Rome, May 29, 1672, wearing men's clothes under their petticoats, and making believe that they were going for a drive." (The Living Age, Vol 187: 479)

Hortense Mancini's lovers were:

1) Anne Lennard, Countess of Sussex (1661-1721)

"Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin, escaped a failed marriage and spent many years in Europe as a courtesan to men of nobility who could afford to keep her. By 1676, she had succeeded in replacing Louise as Charles’s favored mistress. Hortense quickly fell from favor, she was in a lesbian relationship with Anne Fitzroy, Charles' daughter with Barbara Palmer. This ended when Anne’s husband sent her to the country after Hortense and Anne had a public fencing match in St James Park wearing only nightgowns. . . ." (Top 10 Philandering English Monarchs)

2) Aphra Behn

English dramatist, poet &literary writer

|

| Arnold van Keppel 1st Earl of Albermarle |

3) Arnold van Keppel, 1st Earl of Albemarle (1670-1718)

"Her current inamorato was the Earl of Albemarle, Arnold Joost van Keppel, rumored love interest of none other than King William III of England. Van Keppel, however, was adept at this apparent balancing act (as, it appears,was the Duchesse herself) and certainly went on to leap to the heterosexual side of the fence with a vengeance. Hortense was more than twenty years older than the Earl so that the entrance upon the stage of a younger woman creates for us a familiar scenario. Adding stridency to the plot is the fact that this young woman was Hortense's own daughter, Marie-Charlotte, Marquise de Richelieu, who had carried on the family tradition by vaulting a convent wall, having been behind it by her husband and father, to seek her fortune in freedom. . . . " (authorsden)

"After Charles's death in 1685, Hortense remained in England, residing on Paradise Row. . . Although she was in her forties, one of her admirers during the beginning of William's reign was Arnold Joost van Keppel, William's rakish page, who would eventually be made 1st Earl of Albemarle. At the time, Keppel, twenty-three years younger than Hortense, was merely a colonel in the Horse Guards. But then Hortense discovered that Albemarle had fallen in love with her visiting daughter, Marie-Charlotte, and had begun to see her on the sly, the duchess, understandably, fell to pieces. Faced with the ugly fact that her own daughter was her rival, the great beauty deteriorated rapidly. Alcoholism destroyed her looks and her health, and her penchant for high-stakes gambling bankrupted her. She retired to a country home, and passed away there in 1699 at the age of fifty-three. . . ." (Royal Affairs: 226)

". . . Charles Emmanuel II was one of Hortense's suitors during the French's court's journey to Lyon in the autumn of 1658. She dedicates this memoir to him because at the time of its composition (1675), she had been living as his guest in the chateau de Chambery for three years." (Mancini: 27)

"For the first time in her career the fates were really kind to the Duchesse de Mazarin. In Savoy she found the peace and quiet that her naturally indolent temperament craved, and for three years the infatuated Duke supported her in luxury at his Court. Pleasure, of which she was ever a devotee, was agreeably tempered by a taste for literature, art, and philosophy, which she developed at this time. Nor was love abandoned. She shared her heart between the unexacting Duke and a certain Cesar Vischald. It was to the latter that she dictated her memoirs during her stay in Savoy. . . ." (The Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: 38)

|

| Cesar Vischard Abbe de St. Real @Babelio |

French polyglot

"He was born in Chambéry, Savoy, but educated in Lyon by the Jesuits. He used to work in the royal library with Antoine Varillas. This French historiographer influenced the way Saint-Réal wrote history. He used to be reader and friend of Hortense Mancini, duchesse de Mazarin, who took him with her to England (1675)." (Wikipedia)

"César Vichard de Saint-Réal is a 17th century Savoyard man of letters who was interested in all forms of historical writing of his time. He was the historiographer of Savoy . . . In 1675 he was credited with "the Memoirs of the Duchess of Mazarin", of which he was a friend. But we do not know how important his contribution really is." (Caesar of Saint-Réal @Babelio)

.jpg) |

| Charles II of England |

Lover in 1676.

"The teenage Hortense had enjoyed a passionate affair with the future Charles II when he was an exile in France, but at the time the Cardinal didn't think the youth's prospects were adequate enough, so he quashed Charles's hopes of marriage to his vibrant niece. . . ." (History Hoydens, 2007)

"HORTENSE MANCINI was the daughter of an Italian aristocrat and the great beauty of her age. She became the mistress of Charles II in 1675 who was easily enamored by women of great beauty and ambition. The King was passionate about her but gradually cooled to her charms when he learned that she had a lesbian relationship with Anne Lennard, Countess of Sussex as well as the poet Aphra Behn. The King had no tolerance for what he considered “French Dallying.” Her portrait certain portrays her great beauty." (tmooresr, 2010, September 13)

""Hortense's intelligence and sweet disposition had from the first made her the Cardinal's favourite, and after his nephew had offended him he decided that she should be his heir. The report that she was to inherit the Mazarin millions naturally induced many splendid offers for her hand, while her own dazzling charms quickly coloured with a passion for herself. . . It is notorious fact that Charles II, roi sans couronne, twice proposed for her hand, and was twice refused by the Cardinal, who was at the time the ally of Cromwell and not shrewd enough to foresee the future. . . ." (The Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: 22)

"The teenage Hortense had enjoyed a passionate affair with the future Charles II when he was an exile in France, but at the time the Cardinal didn't think the youth's prospects were adequate enough, so he quashed Charles's hopes of marriage to his vibrant niece. . . ." (History Hoydens, 2007)

"HORTENSE MANCINI was the daughter of an Italian aristocrat and the great beauty of her age. She became the mistress of Charles II in 1675 who was easily enamored by women of great beauty and ambition. The King was passionate about her but gradually cooled to her charms when he learned that she had a lesbian relationship with Anne Lennard, Countess of Sussex as well as the poet Aphra Behn. The King had no tolerance for what he considered “French Dallying.” Her portrait certain portrays her great beauty." (tmooresr, 2010, September 13)

""Hortense's intelligence and sweet disposition had from the first made her the Cardinal's favourite, and after his nephew had offended him he decided that she should be his heir. The report that she was to inherit the Mazarin millions naturally induced many splendid offers for her hand, while her own dazzling charms quickly coloured with a passion for herself. . . It is notorious fact that Charles II, roi sans couronne, twice proposed for her hand, and was twice refused by the Cardinal, who was at the time the ally of Cromwell and not shrewd enough to foresee the future. . . ." (The Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: 22)

"Then, in 1659, it was Hortense's turn to have a brush with a royal engagement when the exiled and impoverished Charles II asked her uncle for her hand in marriage. Alas for Hortense, his proposal was swiftly turned down. Of course they might have felt differently had they known that only a few months later, Charles II would regain his throne and be invited back to England to rule again. Mazarin effected a rapid about face and offered Charles an astonishingly huge dowry of 5 million Livres to take on his favourite niece as his bride, but Charles, perhaps still chagrined and humiliated by their reaction to his original proposal turned down both Hortense and her money." (The Stuart Kings)

7) Chevalier de Couberville

" . . . A few weeks later, however, the Duc de Nevers arrived at Milan, and soon discovered the real cause of Madame de Mazarin's taste for solitude. She had, it transpired, conceived a violent fancy for Couberville, the equerry whom the Chevalier de Rohan had given her to escort her to Italy, and who had gained such ascendancy over her that she even denied herself to her brother and sister when he happened to be with her. Soon this affair had become the talk of the city, and people made ribald verses about it, to the intense mortification of the duchess's relatives, who felt compelled, in consequence, to cur short their visit to Milan and remove to Sienna" (Five Fair Sisters: 280)

"Soon after her arrival in Italy, her brother joined his sisters there. But although the three siblings were happy together, they quarreled over Hortense's relationship with Courbeville, a man in her entourage who had accompanied her to Rome. Infuriated, she went to live in the convent where her aunt was abbess, but it did not take long to decide that this abode did not suit her either, and since the nuns now refused to let her depart, she was forced to stage a dramatic escape with Marie's help. . . . " (Cholakian: 86)

"On the night of June 13, 1668, Hortense ran away from her husband, leaving her four young children behind. Philippe [her brother] provided a carriage but remained behind to deflect suspicion for as long as possible. Hortense was accompanied by Philippe's manservant, Narcisse, and her own maidservant, Nanon. Both women were disguised in men's clothing. The group escaped Pris by the closest city gate, the Porte Saint-Antoine, next to the Bastille. At the gate the duchess was met by the Chevalier de Rohan, who had volunteered his squire Courbeville to join Narcisse as an escort. . . The young squire was tireless in his attentions to her needs, spending long hours with her even after Nanon had fatigued. 'I am still persuaded,' she later wrote, ' that my leg would have had to be amputated without him.' The leg healed, and Courbeville was henceforth Hortense's favorite, to the consternation of her other servants. It soon became clear that his nights in Hortense's room had a new purpose. When Philippe set out to join the travelers, he became furious upon learning that his sister and Courbeville had become lovers. . . By the time the traveling party resumed the return voyage to Rome, more than four months had passed his Hortense's initial departure from Paris. Tensions in the family group were growing for several reasons. . . To complicate matters, Hortense's intimacy with the young squire Courbeville was by now quite open, angering both Marie and Philippe, who demanded upon arriving in Rome that Courbeville be sent back to France. . . Her attachment to Courbeville had been born with her newfound freedom and she resisted the pressure to break off the affair, which she knew full well could only severely damage her chances of a favorable settlement in the legal dispute with her husband. . . . " (The King's Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini)

"Hortense Mancini was an incredibly beautiful woman whose bohemian ways appealed to both sexes. An accomplished and skillful rider she could also shoot and fence and enjoyed long country walks either cloaked or in men's clothing. But she had a chequered past and was quite amoral. After running away from her husband because of his cruelty, she gave birth to a child whose paternity was attributed to the Chevalier de Rohan's page, to whom she had taken a violent fancy. She was not therefore suitable company for such a young and impressionable girl as Lady Sussex. Nevertheless she made an instant conquest of her and they soon became boon companions." (Royal Sex: Mistresses & Lovers of the British Royal Family)

|

| Louis I of Monaco |

Lover in 1675.

" . . . She was also having an affair with Louis I Prince of Monaco, and when Charles found out he cut off her allowance. Although he gave in after a few days, this was the beginning of the end of Hortense’s position. She and Charles remained friends. . . ." (Derrick).

" . . . It happened a few months after her arrival in London, the Prince of Monaco visited the capital. Young in years, handsome in person, and extravagant in expenditure, he dazzled the fairest women at court; none of whom had so much power to please him in all as the Duchess of Mazarine. Notwithstanding the king's generosity, she accepted the prince's admiration; and resolved to risk the influence she had gained, that she might freely love where she pleased. Her entertainment of a passion, as sudden in development as fervid in intensity, enraged the king; but his fury served only to increase her infatuation, seeing which, his majesty suspended payment of her pension. The gay Prince of Monaco in due time ending his visit to London, and leaving the Duchess of Mazarine behind him, she, through the interposition of her friends, obtained his majesty's pardon, was received into favour, and again allowed her pension." (Molloy: 158)

"Hortense Mancini arrived in England in the winter of 1675, ostensibly on a visit to her cousin Mary of Modena, recently married to James Duke of York. . . Hortense, however, overreached herself, and a flirtation with the Prince of Monaco caused her to be dismissed, to the delight of her rival. National sentiment was against her, and many must have questioned, as Andrew Marvel did: 'That the King should send for another French whore, When one already hath made us so poor.'" (Historical Portraits)

" . . . She was also having an affair with Louis I Prince of Monaco, and when Charles found out he cut off her allowance. Although he gave in after a few days, this was the beginning of the end of Hortense’s position. She and Charles remained friends. . . ." (Derrick).

" . . . It happened a few months after her arrival in London, the Prince of Monaco visited the capital. Young in years, handsome in person, and extravagant in expenditure, he dazzled the fairest women at court; none of whom had so much power to please him in all as the Duchess of Mazarine. Notwithstanding the king's generosity, she accepted the prince's admiration; and resolved to risk the influence she had gained, that she might freely love where she pleased. Her entertainment of a passion, as sudden in development as fervid in intensity, enraged the king; but his fury served only to increase her infatuation, seeing which, his majesty suspended payment of her pension. The gay Prince of Monaco in due time ending his visit to London, and leaving the Duchess of Mazarine behind him, she, through the interposition of her friends, obtained his majesty's pardon, was received into favour, and again allowed her pension." (Molloy: 158)

" . . . As usual the the Duchess let her heart get the better of her head; she flung herself, cost what it might, into the arms of the dashing Prince of Monaco, who was on a two months' visit to the English Court and stayed two years for the sake of La Belle Mazarin. Her political role was over, and perhaps to no one connected with this intrigue did it give greater relief than to the protagonist herself. . . ." (The Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: 43)

" . . . She was also having an affair with Louis I Prince of Monaco, and when Charles found out he cut off her allowance. Although he gave in after a few days, this was the beginning of the end of Hortense’s position. She and Charles remained friends. . . ." (Derrick).

" . . . It happened a few months after her arrival in London, the Prince of Monaco visited the capital. Young in years, handsome in person, and extravagant in expenditure, he dazzled the fairest women at court; none of whom had so much power to please him in all as the Duchess of Mazarine. Notwithstanding the king's generosity, she accepted the prince's admiration; and resolved to risk the influence she had gained, that she might freely love where she pleased. Her entertainment of a passion, as sudden in development as fervid in intensity, enraged the king; but his fury served only to increase her infatuation, seeing which, his majesty suspended payment of her pension. The gay Prince of Monaco in due time ending his visit to London, and leaving the Duchess of Mazarine behind him, she, through the interposition of her friends, obtained his majesty's pardon, was received into favour, and again allowed her pension." (Molloy: 158)

"Hortense Mancini arrived in England in the winter of 1675, ostensibly on a visit to her cousin Mary of Modena, recently married to James Duke of York. . . Hortense, however, overreached herself, and a flirtation with the Prince of Monaco caused her to be dismissed, to the delight of her rival. National sentiment was against her, and many must have questioned, as Andrew Marvel did: 'That the King should send for another French whore, When one already hath made us so poor.'" (Historical Portraits)

" . . . She was also having an affair with Louis I Prince of Monaco, and when Charles found out he cut off her allowance. Although he gave in after a few days, this was the beginning of the end of Hortense’s position. She and Charles remained friends. . . ." (Derrick).

" . . . It happened a few months after her arrival in London, the Prince of Monaco visited the capital. Young in years, handsome in person, and extravagant in expenditure, he dazzled the fairest women at court; none of whom had so much power to please him in all as the Duchess of Mazarine. Notwithstanding the king's generosity, she accepted the prince's admiration; and resolved to risk the influence she had gained, that she might freely love where she pleased. Her entertainment of a passion, as sudden in development as fervid in intensity, enraged the king; but his fury served only to increase her infatuation, seeing which, his majesty suspended payment of her pension. The gay Prince of Monaco in due time ending his visit to London, and leaving the Duchess of Mazarine behind him, she, through the interposition of her friends, obtained his majesty's pardon, was received into favour, and again allowed her pension." (Molloy: 158)

" . . . As usual the the Duchess let her heart get the better of her head; she flung herself, cost what it might, into the arms of the dashing Prince of Monaco, who was on a two months' visit to the English Court and stayed two years for the sake of La Belle Mazarin. Her political role was over, and perhaps to no one connected with this intrigue did it give greater relief than to the protagonist herself. . . ." (The Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: 43)

| Louis XIV of France |

Lover in 1661.

"His first love was Maria Mancini. She was the niece of Cardinal Mazarin. . . Louis fell in love with her and they were several years together until he had to marry Marie-Therese of Austria." (Louis XIV's Women)

"His first major mistress was Marie Mancini between 1657 to 1660. . . ." (Louis XIV)

"For a brief while it looked as though the loveliest of the Mancini girls, Marie, would end up married to Louis XIV himself -- she was his first love ever, but it was not to be and instead she was packed off back to Italy to marry the Prince of Colonna." (The Stuart Kings)

"A few years later, Louis XIV fell in love with Marie Mancini, Mazarin's niece. Ultimately choosing duty over love, in 1660 he married the daughter of the king of Spain, Marie-Therese of Austria, instead. . . ." (Louis XIV Biography)

"His first love was Maria Mancini. She was the niece of Cardinal Mazarin. . . Louis fell in love with her and they were several years together until he had to marry Marie-Therese of Austria." (Louis XIV's Women)

"His first major mistress was Marie Mancini between 1657 to 1660. . . ." (Louis XIV)

"For a brief while it looked as though the loveliest of the Mancini girls, Marie, would end up married to Louis XIV himself -- she was his first love ever, but it was not to be and instead she was packed off back to Italy to marry the Prince of Colonna." (The Stuart Kings)

"A few years later, Louis XIV fell in love with Marie Mancini, Mazarin's niece. Ultimately choosing duty over love, in 1660 he married the daughter of the king of Spain, Marie-Therese of Austria, instead. . . ." (Louis XIV Biography)

|

| Sidonie de Lenoncourt Marquise de Courcelles |

Daughter of: Joachim-Antoine de Lenoncourt, Marquis de Marolles, & Isabella Klara von Kronberg

Wife of:

1. Charles-Ferdinand de Champlais, Marquis de Courcelles (d.1678), Lieutenant-General of the French Artillery, mar 1666.

2. Jacques de Gaultier de Chiffreville, Seigneur de Montreuil et de Tilleul (1642-1724), Captain of the French Queen's Dragoons, mar 1685.

Physical appearance & personal qualities.

"I am tall, have and admirable figure, and the best air possible; I have fine brown hair, which is disposed, as it ought to be, to shade my face, and relieve the handsomest complexion in the world, though it is marked by the small-fox in several places. My eyes as sufficiently large, neither blue nor brown, but between those two colors, and have a particular hue of their own which is very agreeable. I never open them entirely; and though there is no affectation in keeping with them so, yet it is true they thus gain a charm which makes my look the softest and the tenderest that can be seen. The regularity of my nose is perfect. My mouth is not the smallest in the world, but neither is it very large." (The Monthly Review: 506)

"Some censors have chosen to say that, according to the just proportions of beauty, my under lip may be called too protuberant: but I believe that this fault is imputed to me because no other can be found; and that I must pardon those who say that my mouth is not quite regular, when they allow at the same time that this defect is infinitely agreeable, and imparts a lively air to my smile and to all the movements of my face. In short, I have a well-formed mouth, admirable lips, and teeth like pearly; my forehead, my cheeks, the turn of my countenance, are all beautiful; divine hands; tolerable arms, that is to say, rather than: but I console myself for this misfortune, by the pleasure of having the handsomest legs in the world. I sing well, though not much without method; I know enough of music, indeed, to come off pretty successfully with connoisseur. But the greatest charm of my voice is in the softness and tenderness which it inspires; in a word, I possess all the arms of pleasure, and have never yet exerted them in vain." (The Monthly Review: 506)

"Without being a great beauty, (she says) I am one of the most amiable creatures ever seen; there is nothing in my countenance or my manners which does not both please and interest: every thing about me, even the sound of my voice, inspire love; persons the most opposite to me in inclination and temperament are all of one mind on this subject, and agree that no body can look at me without wishing me well." (The Monthly Review: 506)

"I have more with than any body; it is natural, pleasant, playful, and capable also of great things, if I chose to apply them. I have a good understanding, and know better than any one what I ought to do, though I scarcely ever do it." (The Monthly Review: 506)

Lesbian affair with Hortense Mancini.

". . . Shortly after, Hortense began a lesbian affair with Sidonie de Courcelles and was quickly dispatched to a convent for correction. This was not a success, as Sidonie was sent along with her, and the two indulged in a series of schoolgirl pranks at the nuns (sic) expense before escaping up a chimney. . . . " (Dolby)

"Marie-Sidonie de Lenoncourt, Marquise de Courcelles, for a time was incarcerated with Hortense Mancini in a convent. Like Hortense, she fled her husband and was eventually brought before a court, in Courcelles case accused of adultery, in Hortense's of having unlawfully abandoned her husband. The legal cases of the two friends were among the earliest examples in France of published 'memoires' in divorce trials, a genre that proved popular with the public and sparked published discussions of marriage as an institution both in fiction and expository prose." (The New Biographical Criticism: 118)

Personal & family background.

Born heiress of a noble family, Sidonie, who had lost both parents in her infancy, was brought up by an old aunt, an abbess of Orleans. When she was fifteen the orphan, who was as innocent as she was beautiful, was suddenly removed from the pure life of the abbey of Orleans, by order of the King, whose ward she was, and placed at the Hotel de Soissons, then the centre of the gayest and loosest society in Paris. The instigator of this spiritual seduction of Colbert, who, wishing to enrich and ennoble his family, conceived the idea of marrying the heiress to his brother. But at the Hotel de Soissons the lovely Sidonie fired all sorts of ambitions. If Colbert coveted her name and wealth, Louvois lusted for her person.During the intrigues to which she was exposed she was married off-hand to the Marquis de Courcelles, a man devoid of all principle, who helped to corrupt her on purpose on the day of her ruin to get complete possession of her fortune. Surrounded by such pitfalls, it is not surprising that Sidonie fell, and fell noisily. To escape the thought of her villain of a husband, the girl flung herself into the arms of Louvois. This powerful Minister was able to protect her from the designs of de Courcelles for time, but she sought consolation elsewhere, and got herself so talked and written about in the lampoons that deluged Paris and were said to 'temper despotism,' that her husband had no trouble in getting an order from the King to shut her up at Les Filles de St. Marie." (Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: 29)

"Marie-Sidonie de Lenoncourt, Marquise de Courcelles, for a time was incarcerated with Hortense Mancini in a convent. Like Hortense, she fled her husband and was eventually brought before a court, in Courcelles case accused of adultery, in Hortense's of having unlawfully abandoned her husband. The legal cases of the two friends were among the earliest examples in France of published 'memoires' in divorce trials, a genre that proved popular with the public and sparked published discussions of marriage as an institution both in fiction and expository prose." (The New Biographical Criticism: 118)

Personal & family background.

Born heiress of a noble family, Sidonie, who had lost both parents in her infancy, was brought up by an old aunt, an abbess of Orleans. When she was fifteen the orphan, who was as innocent as she was beautiful, was suddenly removed from the pure life of the abbey of Orleans, by order of the King, whose ward she was, and placed at the Hotel de Soissons, then the centre of the gayest and loosest society in Paris. The instigator of this spiritual seduction of Colbert, who, wishing to enrich and ennoble his family, conceived the idea of marrying the heiress to his brother. But at the Hotel de Soissons the lovely Sidonie fired all sorts of ambitions. If Colbert coveted her name and wealth, Louvois lusted for her person.During the intrigues to which she was exposed she was married off-hand to the Marquis de Courcelles, a man devoid of all principle, who helped to corrupt her on purpose on the day of her ruin to get complete possession of her fortune. Surrounded by such pitfalls, it is not surprising that Sidonie fell, and fell noisily. To escape the thought of her villain of a husband, the girl flung herself into the arms of Louvois. This powerful Minister was able to protect her from the designs of de Courcelles for time, but she sought consolation elsewhere, and got herself so talked and written about in the lampoons that deluged Paris and were said to 'temper despotism,' that her husband had no trouble in getting an order from the King to shut her up at Les Filles de St. Marie." (Court Beauties of Old Whitehall: 29)

Marquise de Courcelles's other lovers were:

1. Francois Bruslard du Boulay

"In the meantime, the Marchioness was attended to her husband's country-seat by his mother, who conceived suspicions of her becoming pregnant. Courcelles, being informed of this circumstance, instituted a process of adultery against her, and finally succeeded in proving his charge of an illicit intercourse with one of her servants; dissolving the marriage, and recovering large damages against her. It was thought, indeed, that her beauty an her interest might have led to a more favourable issue, had she not impudently escaped from prison, in company with a new admirer, Brulart du Boulay, a captain in the Orleans regiment. With him she had the hardihood to remain sometimes disguise in Paris; but at last they thought it prudent to retire to Geneva, where their affection does not appear to have been of long duration. On returning to France, she was again arrested, and imprisoned for some years; her trial being protracted by various appeals and revisions. Here the history concludes abruptly; stating that nothing farther is known respecting her, except that, after having several adventures, she fell in love, sur me reteur de l'age, with an officer, whom she married, and with whom she lived happily." (The Monthly Review: 509)

". . . When the Marquise was running away, she chanced to fall in with the Marquis du Boulay, cousin of the Chancellor Sillery. To see her was to adore her; and he became her protector and took her to Geneva. Boulay was as jealous as her husband. . . . " (Society in the Court of Charles II: 200)

2. Francois-Michel Le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois (1641-1691)

French aristocrat & politician

"This woman was Sidonie de Lenoncourt, Marquise de Courcelles, a beautiful heiress, married against will to a man who she could not love. Louvois had been enamoured of her; and her husband and his family, hoping to propitiate the powerful statesman, basely pandered to the minister's passion, and pretended not to see his advances.This so disgusted the unhappy girl, that she sought refuge from an unlawful which was repugnant, to another which was equally culpable. . . . " (Two Life-paths: A Romance: 137)

|

| François de Neufville de Villeroy c1834-37 @Wikipedia |

2nd Duc de Villeroi

Marshal of France & Madeleine de Créquy, mar 1617

Husband of: Marguerite-Marie de Cosse-Brissac (1648-1708), mar 1662.

The giddiest woman in France.

". . . She encouraged the attentions of the Marquis de Villeroi, to whom she had been passionately attached before her marriage; and her husband, covetous of her wealth accused her of infidelity, and obtained an order for her imprisonment in this forlorn convent. Louvois, jealous and resentful, would not interfere. But he awaited an appeal for his protection from Sidonie herself. This appeal she would not make, and the minister suffered her to be incarcerated. Madame de Courcelles was the giddiest woman in France; it is not therefore surprising that she wept day and night for the loss of the pleasures from which she had been banished. . . ." (Two Life-paths: A Romance: 137)

Husband of: Marguerite-Marie de Cosse-Brissac (1648-1708), mar 1662.

The giddiest woman in France.

". . . She encouraged the attentions of the Marquis de Villeroi, to whom she had been passionately attached before her marriage; and her husband, covetous of her wealth accused her of infidelity, and obtained an order for her imprisonment in this forlorn convent. Louvois, jealous and resentful, would not interfere. But he awaited an appeal for his protection from Sidonie herself. This appeal she would not make, and the minister suffered her to be incarcerated. Madame de Courcelles was the giddiest woman in France; it is not therefore surprising that she wept day and night for the loss of the pleasures from which she had been banished. . . ." (Two Life-paths: A Romance: 137)

5. Jacques de Rostaing de La Ferriere.

Hortense Mancini, Duchesse de Mazarin Gallery

%2C_Duchess_of_Bouillon_by_Benedetto_Gennari.jpg/656px-Marie-Anne_Martinozzi_(n%C3%A9e_Mancini)%2C_Duchess_of_Bouillon_by_Benedetto_Gennari.jpg) |

| Marie-Anne Mancini Duchesse de Bouillon bef 1715 |

5) Marie-Anne Mancini, Duchesse de Bouillon (1649-1714)

|

| Maurice-Godefroy de La Tour d'Auvergne Duc de Bouillon 1657 |

References for the Mazarinettes:

%2C_%D0%B3%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%86%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%B0_%D0%B8_%D0%BA%D0%BD%D1%8F%D0%B7%D1%8F_%D0%9F%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BE.jpg)

,.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment